Delivery skipper Ben Lowings examines how different popular rudder designs affect handling, and explains how to maintain them

Retiring from an offshore race once because I deemed that a broken mainsail batten made it too dangerous for the yacht to continue, it was only when tied up in Falmouth that the crew noticed a more serious problem with the rudder.

To the crew’s credit, although tired from racing, all lent a hand in addressing the problem, with bodies bent double and heads craned into areas to test play in the steering quadrant and view as much of the rudder system as they could with the boat still in the water.

Out of sight is out of mind quite often with a sailing yacht’s rudder.

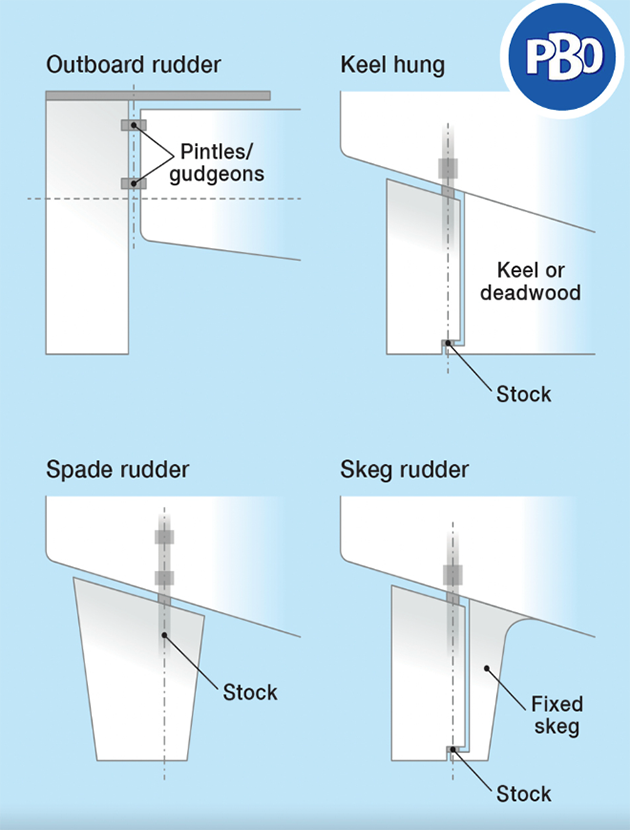

Boat rudders and how they are attached to the yacht

It answers when we turn the wheel and even supplies us a little haptic feedback as reassurance when under way, or quite a truckload on a boat with serious weather helm.

Boat rudders nevertheless demand our attention throughout their lives.

Boat rudders are difficult to consider independently. A sailing yacht’s lines on paper only suggest its behaviour.

Only by taking it on the water can you really appreciate its ability to turn and track.

These competencies have as much to do with the shape of the hull and the keel as much as they are to do with the rudder.

The rudder is only one element in a boat’s underwater foils. They feed into so many other issues of design.

To comprehensively discuss rudder design in detail would take a book, so what follows is the basic principles of popular rudder designs and how they affect handling.

Boat rudders: Concepts

A rudder is, in essence, a blade, twisted in the water to direct a vessel.

The first one was probably a sculling oar, held by hand, off the stern of a boat: early evidence for this comes from Egyptian barges.

The Vikings were the most famous adherents of the practice of steering their ships by hanging a direction-giving oar over the starboard (‘steerboard’) side.

Most modern craft hang their rudders along the midships line, on the line between bow and stern.

Yacht rudders are most usefully considered as both the blade and the materials fastened to that blade to manipulate it.

These connections – whether they be thumb-sized pins or large port sockets to accommodate a rudder stock – are crucial to the rudder concept.

As with sails above water, the idea of ‘centre of effort’ is vital to the foils underwater.

Balanced spade rudder

Spade rudders may suffer more than others in the event of a grounding. Credit: Graham Snook/Future PLC

The spade-like attachment on a racing yacht gives the tiller or wheel grip on the water.

They’re highly thought of for maximising control of the vessel’s motion.

With a fin keel, they will be responsive to even the helm’s slightest movement. Spade rudders are best for tight turns.

They are also best for catching weed, fishing line and other detritus.

Balancing (itself a key concept in rudder design) comes into its own here as a free-hanging rudder that is balanced (i.e. has a section of the blade in front of the rotating stock) is excellent at maintaining control under engine, especially going astern.

Performance yachts like balanced spade rudders as they are particularly efficient at turning.

Although efficient in planes close to the vertical, as they tip a spade can, in a way, be ‘too efficient’, and act like an aeroplane’s wing under the water.

This air-sucking to one side can create drag, and even pull the stern into the water when the vessel heels.

It is possible to exaggerate here, but efficiency can bring complications.

With twin rudders, the helm retains control even when pushing the boat hard

Boat rudders are designed to have the appropriate buoyancy so neither pushes the hull up nor drags it down when the vessel is afloat.

That is in a perfect world, however. It is a small risk comparatively, but buoyancy in a spade might even lift the boat when the hull tips to the side.

Nearly all twin rudders are high aspect ratio spades.

They behave as individual spade rudders do, although they are offset from the centre line.

The main thing to be aware of in the twin-spade setup is that prop wash will go between the blades.

Your steerage only comes when way is on, i.e. when water is pushed over the blade as the boat moves.

Skeg rudder

A skeg rudder can shape and direct water flow efficiently. Credit: Graham Snook/Future PLC

Skeg rudders take their name from the Old Norse word for ‘beard’ (skjegg).

On a surfboard, the skeg is the fin, the only foil, whereas on a yacht, it is the trailing foil when under way forward.

A skeg is, in this circumstance, the static leading edge of the rudder appendage, with the blade trailing behind.

Although less vulnerable than a spade to catching weed and ghost gear, line can still get stuck between the skeg and the blade.

Arguably, freeing this debris is harder than with a spade rudder because it’s enclosed between components.

That said, with a spade rudder, only the keel is shielding its leading edge from impacts; the skeg will always offer the blade some protection.

Naval architects will mention that a skeg actively shapes how the water flows around the blade.

Fashioning that flow to concentrate on a certain point makes the boat turn more quickly and smoothly.

Keel-hung rudder

The keel-hung rudder of the OE32 is hung off the trailing edge of the keel below her North Sea transom. Credit: Katy Stickland/Future PLC

In some ways, skegs give you the advantages of a traditional keel-hung rudder without having the long keel.

Long keels, of course, have their chief merit in stability.

Reversing into a tight berth with a barn-door rudder on a long, deep keel is an entirely different proposition from trying the same on a light displacement craft using twin spade rudders with high aspect ratios (i.e. tall and narrow).

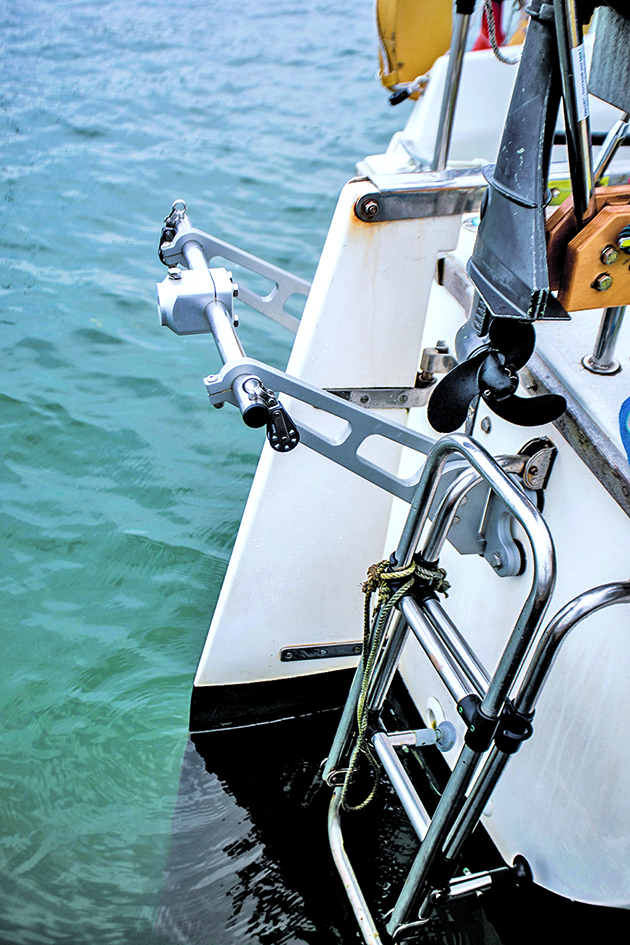

Outboard rudder

The transom-hung outboard rudder is vulnerable to impacts from astern. Credit: Richard Langdon

The outboard rudder is the other main concept in design.

The blade is attached straight to the transom or a sternpost. There’s no slant back towards the trailing edge of the keel.

It’s very much an appendage.

In this class are servo-pendulum rudders. They form part of wind vane self-steering systems that are vulnerable on long passages.

A well-known weakness of an over-the-transom rudder is that it is prone to impacts from astern.

Ask anyone who’s had their dinghy back unintentionally into another, or even the committee boat.

Look at the trailing edge, as that’s where you’ll get information on its usage. It will tell the story of those impacts…

Construction of boat rudders

Looking more closely at how boat rudders are built, most are fashioned around a stainless steel or aluminium tube (sometimes solid metal).

This stock is the link to the wheel or tiller. For a spade, it’s what connects the rudder to the boat.

As they are moving parts, thought should be given to how the stocks are lubricated.

Ports can allow grease into the tube, but often they are relatively inaccessible.

It’s important to consider how the stock is connected to the rest of the blade.

A standard rudder comprises a filled or hollow structure around a metal stock and tangs

Sometimes, the interface between the tube and the blade is the only connecting surface.

That connection has to be super strong for the rudder to be effective for any length of time.

It is regarded as very difficult to maintain a perfect seal between the composite blade and the metal stock.

With a typical glass-reinforced glassfibre blade, bonding to a tubular piece of metal is likely to be weak.

Mostly, it is not sufficient to deal with repeatedly shoving a water load from side to side, and it will quickly fail.

Thus, the quality of this connection is usually improved by fastening the stock tube to a metal bar, or several metal bars, or even better, a grid-like framework that buttresses the blade from within.

The GRP blade skin has a lot more metal surface area to adhere to when it covers a grid or frame.

Even if the metal is sturdy, if the welding is not extensive (and most of these things are just spot-welded), then there are more opportunities for failure.

It is important to keep rudder stocks lubricated. Credit: Mark Ryan

Glassfibre matting is wrapped around a foam core, but more usually, two shells are then stuck together to encase the stock and cored frame.

Those shells are comparatively fragile and easily pierced. The interface between the two shells is a common point of failure.

A mirror can help you see the top of the blade where the stock enters the shell and onto the framework; again, another danger area.

The bonding inside a rudder blade is very vulnerable, out of sight and usually deep underwater.

Many rudder problems arise from damage to this internal structure; a split or unsealing which does not seem critical because it is very hard to see.

When your rudder is answering as well as an old paddle trying to swill a barrel of barley mash, stainless steel inside the rudder tube may have long rusted unseen.

The stock will need a look.

As for the soggy-blade sort of rudder failure, one of the best descriptions is from the American seaman, George Michelsen Foy.

His yacht Odyssey was being given a going-over by a surveyor. The GRP casing around the rudder was ‘as waterlogged as pound cake left in strawberry syrup overnight’.

Survey

When underway and afloat, the obvious test is whether the rudder does what you tell it to do.

Perhaps (given the nature of yachting as shepherding a sometimes truculent boat in a certain direction), the more likely test is whether the rudder does not actively obstruct you in carrying out a certain manoeuvre.

Diving underneath and wiggling the rudder (when you are not making way) might not only be uncomfortable but might also give a misleading impression of the forces the foils are under when the yacht is driving forward, as its designers envisaged.

Yes, sight of the rudder will give an immediate confirmation of any calamitous breakage.

A gash in the leading edge of a spade would be good to have identified.

But, afloat and underway, sometimes to behold a rudder half-chewed off by an orca might be reassuring in the sense that the assailants have swum off, and you can see there is something left of the rudder, instead of a hole in the boat.

Inspect the rudder surface for any form of water ingress, blistering or splits. Credit: Graham Snook/Future PLC

Once out of the water, a proper survey can take place.

Bear in mind that being afloat may have given you a kinder view of any issues, as rudders are in their natural element when in the water.

Buoyancy on the blade may have pushed the stock up to an optimum level in the tube; out of the water, the rudder might be hanging on a bearing it’s not supposed to do for any length of time.

The grittiness you might get when manipulating the blade might just be you feeling resistance against this bearing.

Remember not to remove the bearing or anything else that might be keeping the rudder from dropping out completely.

Sometimes it’s necessary to lower the rudder in a controlled fashion to examine the portion of the stock heading up into the rudder tube.

The appropriate connections need to be loosened, but no more.

Rudder repairs often lead to a rebuild. This example shows a bad case of water ingress. Credit: Mark Ryan

Damage to the base of a rudder because it clonked down onto the yard concrete is not completely unknown.

How many times have you walked around the hard-to-see dropped rudders sitting on their own weight on a stack of breeze blocks?

When testing for play, the best thing to do is grab the blade with both hands and try to shove it sideways.

First, though, you should screw in the lock on the steering wheel so it can’t turn.

If you have a tiller, then it’ll need to be lashed very strongly to one side.

Fixing it midships this way may seem apt for a rudder alignment check, but otherwise it would bend or break the tiller arm.

Assessing your rudder means looking at what materials are used and how they complement each other.

Water swelling a foam-core rudder can bulge out the GRP skin, which has been puffed out to accommodate growth.

The blister can stay out even if the foam core contracts owing to temperature changes. Impacts can split the seam on a GRP shell case.

Some long-distance boats use a wind vane steering system as an emergency rudder, while those offshore in small boats, like the Jester Challenge skippers, prepare by having a spare rudder that fits in the outboard well. Credit: Jake Kavanagh

Frost-shattering tears it longitudinally open. A metal stock offers fortitude.

But if it bends, it can jam the rudder completely.

A composite rudder stock would probably, in the same situations, just snap off instead.

A lightweight aluminium tube will serve you well as a rudder stock for day sailing; less so for rigorous offshore passages.

A bent pintle is in many ways worse than a corroded one.

If you have a block preventing the gudgeon from riding up or down and then disconnecting, it is critical to monitor any movement in it.

When it comes to rudder stocks, stainless steel is preferred to mild steel; there is debate over whether stainless steel or bronze is best for fittings, such as pintles.

If you decide on stainless steel, make sure you fit a zinc anode nearby. Corrosion here can be very obvious.

Arthur Ransome wisely noted that spotting corrosion to rudder fastenings can help you a great deal when bargaining with a seller.

He was perusing various boats on a beach in Estonia when he found his yacht, Kittiwake.

The vendor had been trying to push a high price on account of her excellent potential for smuggling apples. The renowned yachtsman invited the seller to show him the crumbling rudder – and the rest is history.

Rudder repair

To repair your rudder is good seamanship. It puts you in good company.

Christopher Columbus and Vito Dumas, the first person to sail solo around the world south of the three great capes, both had to put in to the Canary Islands to fix the steering blades for Pinta and Lehg II, respectively.

The extent of repairs depends on the number of problems you (and your surveyor) have identified, but also the time and money available.

With the sodden morass that was the rudder on George Foy’s Odyssey, a boatyard carpenter blithely assured the yachtsman that the rudder looked strong enough.

‘All I need do is drill a hole to let out humidity, and patch it later.’

If that seems a little slapdash, perhaps a more thorough repair would be to drill a number of holes, starting from the base.

Or there could be a pattern of holes evenly spaced over the whole surface of the blade.

Then, if the blade is rested horizontally and ‘hung out to dry’, as it were, there’s a good chance the water will not only drain completely, but the interior of the blade will have a chance to recover some strength.

Being thorough

A really thorough repair would involve cracking open the shell seam with the appropriate tool (usually a circular saw).

The incision should usually be on the trailing, thinner edge to make things easier when you put it all together again.

Repairs for boat rudders quickly go into rebuild territory.

And it may seem straightforward, with a rudder stock that’s been slightly bent, to just bend it back.

Even though it’s now straight, the weakness introduced by the first bend will have been compounded by the correction.

A new stock may be required, or a new rudder.

If a stock extends only just below the top of the rudder, then that join takes an enormous amount of pressure. Fresh welding is a likely option.

A handy way of reinforcing the frame is to insert steel triangles between the bars and stock, thus increasing the surface area for attachment.

Reinforcement may be most effective above the bottom of the hull, bringing the stock up to a new bulkhead or buttressing it closer to deck level.

There’s no point in having a bulletproof rudder if the hull that supports the rudder stock is not sound.

However, welding can also cause changes to a metal’s microstructure, making it more vulnerable to corrosion.

Boat rudders: pros and cons of popular designs

Deep and semi-balanced, the rudder on the Scanmar 40 is supported by a long skeg. Credit: David Harding

Spade rudder

Pros: light, wide arc, tight-turning, less drag, often high-aspect ratio. Can be sacrificed to save the hull.

Cons: catches weed at the junction with the hull. Leading edge exposed. Structural problems are not normally visible.

Skeg

Pros: leading edge is doubly protected by keel and skeg. Can shape and direct water flow onto the rudder efficiently.

Cons: catches weed all along the connecting joint to the skeg. Structural problems are not often visible.

Keel-hung

Pros: tough, stable. Leading edge protected along most or all of its length.

Cons: heavy, catches weed along the interface to the keel. Structural problems are not normally visible. Often limited arc of movement.

Outboard

Pros: usually the widest arc of movement. Removable and replaceable while making way. Can be sacrificed to save the hull. Structural problems are visible.

Cons: no protection for leading and trailing edges. Exposed to impact on all sides.

Boat rudders: maintenance tips

- Hold the rudder by hand and shake fore and aft: Excessive play is indicative of wear.

- Pivot the rudder by hand laterally: Rough or jumpy movement means problems. Examine the base of the rudder. If it’s leaking, stale seawater has been trapped inside the blade, which requires draining.

- Shake the stock inside the rudder tube: Roughness needs to be eliminated with greasing if possible. If roller bearings are present, then they should only be cleaned.

- Examine the components around the top of the stock tube: Check sealing is intact, and whether there are any cracks in gaiters or stuffing boxes.

- Put the steering hard over, then play the rudder by hand: See if the stops are doing their job.

- Look closely at the top of the stock itself: Splitting here can let water in through the top and let it mull inside the blade.

Arcona yacht sinking: Couple share how they tried to save their boat after the rudder stock broke

Ingmar and Katarina Ravudd tell PBO about the steps they took to save their Arcona yacht after a broken rudder…

Orcas left us rudderless! Yacht couple tell of terrifying ordeal off Spain

Zoe Barlow shares her experience of losing a rudder during sustained attacks by orcas whilst sailing her Sun Odyssey 40…

‘The steering wasn’t working. I felt my stomach sink’ – rudder failure in the Pacific

Steering loss aboard a Maxi 120 mid-Pacific reminds Charlie Pank of a previous rudder failure on a Beneteau Idylle many…

How to build a rudder for your boat

Hitting a submerged object destroyed Mike Gudmunsen’s rudder...so he set about making a new one

How do you close the gap between the rudder and propeller?

Practical Boat Owner reader David Blackborow is trying to find out the best way to close the gap between the…

Want to read more articles like Boat rudders: everything you need to know?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter