Ali Wood gets top tips on what to look for in a trailer-sailer, and how to get the best of both worlds for road and water.

Ever considered getting a trailer-sailer?

Some think they might just be for pottering around harbours, but they couldn’t be more wrong. Over the years PBO has met owners who’ve sailed thousands of miles in theirs; battling Force 7s in open water, and even crossing the North Sea.

Of course, harbour-hopping and creek-crawling does have its appeal. What could be nicer on a sunny weekend than launching in calm waters where you can enjoy ‘pure sailing’ but with the safety of an outboard, plus any number of lunch and overnight spots where you can drop the anchor?

The smaller your boat, the less money you’ll have to spend on maintenance, leaving more time for fun on the water. If you can trail it too, you’ll never get bored of cruising ground.

Trailer-sailers, you might deduce, require a trailer to transport your boat to a slipway and, unlike a dinghy trailer that lives at the club, this needs to be roadworthy. The advantage, of course, is you can drive to wherever you want to launch, and sleep on board in the cabin or under a boom-tent.

Boats with more accommodation allow for weekend and longer cruises and because your boat can live on your driveway, you save on mooring costs too.

Trailer-sailers: where to start

The BayCruiser 26 built by Swallow Yachts. Photo: Swallow Yachts.

Since the 1990s the UK market for new trailerable boats has shrunk, but there are a large number of trailer-sailers on the second-hand market to suit every budget. GRP boats kept under cover (in a shed or a barn) will fare the best.

There are also a few British boatbuilders still making smaller boats, as well as dealers such as Boats on Wheels, that import them from Europe.

Where to start with a trailer-sailer

Picking a trailer-sailer can be bewildering.

PBO’s trailer-sailer expert, Colin Haines, says not to worry too much about finding the ‘perfect boat’ first time.

“Think of your first purchase as a test-bed for your ideas,” he says. “After a season or so you’ll be much wiser about the sort of boat that will actually meet your needs. Old trailer-sailers in good condition barely depreciate, so acquiring an opinion based on a season’s personal experience will not be overly costly.”

What exactly is a trailer-sailer?

A trailer-sailer, as the name suggests, is designed to be towed behind a car.

Larger and heavier than a dinghy or open keel boat, but can be launched by hand, it may also have an enclosed cabin as well as ballast (either fixed, or in a swinging centreboard) making it unlikely to capsize.

Typically you’re looking at 19ft or longer but exactly how big depends on a number of factors.

The sporty Beneteau First 21.7 has a stub keel. Photo: David Harding.

It’s not just about size, explains Hein Kuiper, who runs a trailer-sailer selling business with his wife Hilary called Boats on Wheels. ‘What makes a boat a proper trailer-sailer, as opposed to ‘a small yacht which could be trailered with varying degrees of difficulty,’ depends on several factors including draught, beam, weight and rigging type.

Some larger yachts – such as the Sedna 26 and water-ballasted Dehler 25 – for example, can be launched and recovered in only 40cm of water, while a smaller Beneteau First 21.7, needs 70cm of water to float due to its stub keel which retracts under (rather than inside) the hull.

Draught on a trailer-sailer

On a trailer-sailer, having a shallow draught is crucial. When the keel is lifted, the boat needs to float onto a submerged trailer while the wheels of the towing vehicle stay dry. The last thing your car needs is corrosive saltwater on brakes, bearings and other metal parts. This kind of trailer-sailer needs to float in around 20cm to 45cm of water.

The Parker 21 and 235 are good examples, and have fully retractable centreboards.

Shallower fixed bilge keels are also an option, as long as you’re willing to trade a little on performance.

If the draught is deeper, you could buy a separate launching trolley, such as those seen under dinghies and if you don’t intend to trail, keep your trailer-sailer ready-rigged at the place you like to launch.

When boats have a deeper draught, say over 50cm, then depending on the gradient of the slipway it becomes almost impossible to keep your car axles dry without the use of a long strop or tow bar extension.

But if you don’t mind submerging your trailer or having your boat hoisted in, other shallow draught boats to consider may be the Etap 21i, with its 70cm tandem keel, or the 91cm wing-keeled MG Spring 25 (see page 24). Similarly, the more contemporary Pointer 25 and Pointer 30 (PBO, July 2025).

“If you’re planning on recovering any of these fixed keel yachts onto a trailer then we’d recommend a set of guide posts so you can see where the submerged trailer is as you float your boat on,” says Hein.

Beamy boats, such as this Sedna 26 require a sturdy double-axle trailer. Photo: David Harding.

Beam and height on a trailer-sailer

The maximum trailer width on UK roads is 2.55m, but actually the maximum load width (ie the boat sitting wider on the trailer) is 2.9m. Above this, the boat would be considered a ‘wide load’.

Many popular trailer-sailers are around 2.5m wide but if you’re after more space and headroom you can legally tow a range of boats from the MG Spring 25 (at 2.75m wide) right up to the Pointer 30 (at 2.9m wide).

“The real question is not what is technically permitted but whether a 25ft boat can be easily towed behind a normal car,” says Hein. “Most big 4×4 cars are a little under 2m wide. Most caravans are only 2.55m wide. So, you’re towing a load which is 3ft wider than most cars and a foot wider than all caravans. Picture yourself doing that on a Cornish B-road!”

Weight is also a consideration for beamier trailer-sailers. Most will be out of the towing range for your average car.

There’s still space in this Sedna 26 saloon around the keel casing. Photo: David Harding.

So if you’re considering a yacht that spends its winter on a trailer and will only be moved a handful of times (and you have the right car), it’s OK to think big. Otherwise, it makes sense to stick to the 2.5m beam.

Height is also a consideration. When you’re trailing, the mast will be sitting on top, and you need to consider obstructions such as bridges, especially on local roads. Even fairly modest boats should allow about 2.5m height. Keels can protrude underneath the boat even when raised, and combined with a high freeboard, can make the boat on a trailer quite a high vehicle.

On the other hand, low topsides combined with a low cabin – for example, with the Pointer – make the boat more trailerable.

Weight

Unless you’re willing to upgrade your car, the trailer-sailer you buy may have to be determined by your towing capacity.

A ‘true trailer-sailer’ according to Hein needs to weigh in at around a tonne (1,000kg) or less.

“If you have a small or modest family car, then you’ll be more limited in what you can tow behind you, and I’d suggest something like the Astus trimaran or one of the smaller Swallows.”

Swallow Yachts, for example, produces the water-ballasted BayCruiser 21 (600kg) and 23 (850kg) – albeit with limited accommodation – while the racy Beneteau First 24 (985kg) makes use of resin infusion, but comes at a higher cost. Buckley Yacht Design’s BTC-22 displaces only 940kg at a more affordable price.

Trailer-sailer trimarans such as the Astus 20.5 (500kg) and 22.5 (650kg) dispense of ballast altogether, relying on their float buoyancy and width instead. However, the floats can be retracted for towing, meaning you can use an ordinary family car to tow them.

Consider how easy it is to raise the rig. Photo: Graham Snook.

Any car can technically be fitted with a tow bar, but it should be done professionally through a garage or bespoke fitter, who will connect the electrics too. What’s important is the towing limit for the car, which will be specified in the manual and determines the weight of the boat and trailer you can permit yourself.

“If you’re looking at ballasted boats in the 23ft-plus category they quickly exceed the 2 tonne mark with a trailer,” warns Hein. “Also, most electric vehicles will struggle with a high towing weight, so really you will probably need a combustion engine for the moment.”

The more popular trailer-sailers tend to weigh around 1.25 tonnes or more (for example, the Jeanneau Sun 2000 and Beneteau 21 series), and when you add a 450kg trailer, boat inventory, fuel and water, you can quickly top 1.8 tonnes, so will need a large family car such as an Audi A6 or a Ford Galaxy.

Beamier boats, such as the Sedna 26 or MG Spring 25, weigh in at 2 tonnes plus another tonne for a sturdy double-axle trailer and inventory, requiring a substantial SUV to tow them.

However, if you’re after a 25-footer, there is some variation in weight range, says Hein.

“While the Jeanneau Sun 2500 weighs in at over 2.2 tonnes, the Pointer 25 weighs only 1.5 tonnes. If you don’t mind sacrificing sailing characteristics for space and headroom, the Viko S26 comes out somewhat better with two keel versions, both claimed to be under 2 tonnes (1,650kg & 1,800kg).”

Getting the rig up can be a two-man job. Photo: Graham Snook.

At the larger end of the trailerable scale, you also need to consider where you’ll launch, says Colin Haines. ‘Trailerable boats’ travel on trailers that lack recovery winches and need the services of a boatyard to be launched and recovered.

“If it’s a sailing club slipway, then no problem, but if you’re looking at a shingle beach, for example, for a boat of around 1,750kg (1.75 tonnes) or greater this would be a challenge even for a serious 4×4 tractor, as the wheels will sink.

Raising the rig on a trailer-sailer

One of the biggest challenges, especially when short-handed, is getting the rigging up.

There’s a wide array of mast lifting approaches depending on the type of boat, advises Hein.

One, for example, is using a gin pole, which is basically a spinnaker (or bespoke) pole which sits in a hole or bracket at the foot of the mast. Another is an A-frame which sits at a 90° angle to the mast and, on a 21ft boat, is about 6-8ft up. A block and tackle or winching system then provides the pulling power.

“These things are often part and parcel of the boat,” he says. “I’ve seen systems where the whole mast and boom is spring-loaded and drops in minutes. You also need some kind of tabernacle so the mast can physically pivot.”

The Poles are good at designing mast folding gear, such as this elaborate system we encountered on an Antila 33.3 during a yacht charter with Undiscovered Sailing. Photo: Ali Wood.

Some trailer-sailers are easy to rig. For example, gaff-rigged boats such as the Cape Cutter 19 or Cornish Shrimper 19 have tall mast tabernacles on the coachroof and relatively short wooden masts which can be raised single-handed at a push.

For the more common mast-top or fractional aluminium rigs, the challenge is greater.

The longer and heavier the mast, the harder it is to push up and control. Even medium-sized trailer-sailers such as the Beneteau 21-footers require at least two crew, ideally more to get a mast up.

“Mast stepping causes more stress in trailer-sailing owners than almost anything else,” says Hein. “You have a few choices: either go for a small and light boat, enlist the help of volunteers, hire a crane or use some of the ingenious mast lifting systems which manufacturers have dreamt up.”

Cables are a critical element of a lifting kit, enabling the mast to be raised without lateral movement causing damage. Long masts need a support post or cradle to stop them crashing onto the coachroof.

Beneteau and Jeanneau have mast lifting kits for their smaller cruisers, involving a gin-pole complete with stability cables. The Astus boat range, having been designed for short-handed trailer sailing, has simple but effective mast lifting kits too.

Keelboats like this J24 can be trailed but will need craning in and out of the water. Photo: Alice Driscoll.

“The best examples of mast lifting kit we’ve seen come from Poland, where they know a thing or two about mast raising,” says Hein. “On boats such as Sportinas and Vikos the mast lifting kit consists of a robust pivoting A-frame which is permanently fixed to the deck and integrated with the forestay/furler. Even in the 25ft+ group of yachts, the Polish boats fare rather well with both the Sedna 26 and Viko S26.”

When PBO did a charter in the Masurian lakes, we had a mast folding kit on our 33ft Antila yacht, which we lowered and raised with ease to get under bridges.

About the trailer

The weight of a trailer is proportionate to the size of boat it carries. With the exception of aluminium trailers, the rule of thumb is around 40%. You can check your car’s towing capacity by looking at the VIN plate (see panel, right). And check your driving licence – you may be prohibited from towing a trailer with a 23ft boat on it.

Most trailer-sailers are sold with the trailer, and the builder will commonly source these to ensure it’s the right specification and quality for the weight and size of boat. If the boat you’re after doesn’t have a trailer, there are several good brands in the UK such as Extreme and SBS, which can help you spec out the right trailer for your vessel.

Your first trailer-sailer tow

Towing a boat for the first time can be daunting, and there are two common issues to look out for.

Snaking tends to happen when there’s too much weight at the back of the trailer, meaning the nose or ‘hitch’ weight is too light. The solution is to move the axle back along the trailer, bringing the centre of effort forward, where the weight can be supported most effectively.

“Most trailers can be set up so you can move the boat or the axle about to suit the weight distribution,” explains Hein. “With a RIB, where the majority of weight would be in the engine, the weight is further back, but with trailer-sailers carrying ballast, the weight tends to be more in the centre so the axle is further forward on the trailer.”

The opposite problem is having too much weight forward, as that places it on the hitch and coupling. Each car tow bar comes with a maximum weight bearing capacity of around 100kg to 150kg – more than that and you’ll damage the towbar.

Remember that when towing you can’t go at the same speed as other traffic, and when you brake you’re braking for the whole weight of the thing behind you. Most trailers, if carrying over 750kg, need their own brakes. When the car stops a compression effect in the coupling of the trailer applies the trailer brakes.

“You’ll need more stopping distance and should give yourself very wide turning circles. The most common problem is people scraping their boats when cornering” advises Hein.

“A lot of people worry about reversing down a slipway with a large lump behind them. People struggle with pointing the boat in the right direction; you need to turn in the opposite way to when reversing the car. Have someone there to guide you. Obviously, the time you get it wrong there’ll be lots of people watching… but don’t worry too much, I’m still learning too!” Hein says.

How to tow and launch a trailer-sailer: tips from James Gibb

A few years ago I was approaching retirement and needed something to fill my time. I considered various types of boat and quickly realised that, living in East Yorkshire but with a penchant for sailing on the west coast of Scotland, I needed a vessel that could be trailed home for the winter. Planning for a trailer-sailer cruise was my best option.

I had a ready-made base at Tayvallich in Argyll, which was where I’d keep the boat for the summer. I considered various lightweight vessels but all had their drawbacks.

Then I saw the Varne Folkboat, Free Spirit.

Now, I’d had previous experience sailing a Folkboat and knew all about their capabilities from the likes of Blondie Hasler and Mike Richie. I also knew that with the right equipment, a Folkboat could be trailed, so a deal was done.

The problem with a Folkboat is that you need a fairly substantial trailer and a good towing vehicle. Fortunately I found a suitable twin-axle steel trailer that, after some minor modifications, was just the job. A twin-axle (four wheel) trailer is essential for a boat of this size and weight in order to provide adequate stability and weight distribution. First problem solved.

James Gibbs’s Varne Folkboat, Free Spirit, and his Land Rover Discovery tow vehicle. Photo: James Gibb.

As for a suitable towing vehicle, my son has a 1994 Land Rover Defender, which proved to be excellent, both for bringing Free Spirit from the South Coast to Brough and for going to/from Argyll. On retirement, I subsequently obtained a 1996 Land Rover Discovery, which does the job just as well.

Launching was now the next headache to overcome and although it’s possible to run the loaded trailer down a ramp, this was a very definite no-go for several reasons. A word of warning: don’t rely on the advice of a boat supplier who says you can launch using your road trailer.

Firstly, my trailer is a steel box section with drain holes. This is bad enough if rain water is forced inside but I hate to think of the corrosion problems if immersed in sea water. I pumped as much old engine oil into the sections as best I could to hopefully reduce corrosion. A trailer with angle or I-beam construction can of course be washed off after immersion if this is the chosen method of launching.

However, there is another problem lurking to catch the unwary – the matter of sealing the wheel bearings. Old seals almost certainly will allow water to enter the hubs and thus mix with the grease which, unless you’re very lucky, will result in bearing failure and possible loss of the wheel. Sod’s law says this will happen at night on a remote part of road or motorway.

There are a number of manufacturers who say their bearings are adequately sealed and thus the trailer can be immersed, but in my experience there’s only one safe way and that is to strip each hub and repack with new grease after each immersion. So I don’t immerse my trailer. I now use a local boatyard in Argyll to lift and launch Free Spirit and recover her to her trailer. This also guarantees a good sail to/from her summer mooring at either end of the season.

Another area that has caused problems in the past, but probably not so bad in these days of better regulation, relates to wheels and tyres. Tyres are rated for load and speed and it does concern me at times when I see trailers with small wheels being taken down the motorway in excess of the speed limit. I often ask myself whether or not they were designed for that speed and/or whether the driver is aware of the potential dangers.

With a heavy boat behind, you must always concentrate on what is going on around you. In particular, how quickly can you stop?

Trailer-sailers come in all shapes and sizes and just like having the right equipment at sea, it is just as important to have the right equipment on the road. Think carefully about what you’ll need before you set off on a trailer-sailer cruise.

Duncan Kent recommends essential trailer-sailer kit

There’s a minimum level of equipment you’ll need to keep safe, warm and happy aboard a day trailer-sailer.

Safety kit would usually include lifejackets, a means of communication with the shore (handheld VHF radio or mobile phone in a waterproof bag), navigation charts if you’re in unknown territory (smartphone charts are fine for coastal sailing), handheld GPS, binoculars, compass, an anchor and rode, a powerful torch or two and a couple of handheld flares. Also, make sure someone ashore knows your passage plan, approximate ETA, crew list, hull colour etc.

Then there are the comfort and sustenance considerations. In addition to fresh water and a Thermos of hot drink or water for making soup, it’s a good idea to take energy snacks should you not find time to stop for a proper meal.

Waterproofs and warm, dry clothing are also a must, as is a decent dry-bag to keep them in. Getting wet and cold not only spoils the day, but it can be dangerous if it starts to affect the mental and physical abilities of the crew.

Finally, you might want to add a few luxuries, especially if you plan to sleep on board. A portable loo is handy for long days and nights, and a single-ring cooker is all you need if you’ve pre-prepared a one-pot supper – and don’t forget a frying pan (and the bacon!) for breakfast. A good lantern is handy and if you’ve got the kids with you don’t forget to take something for them to do, read or play with.

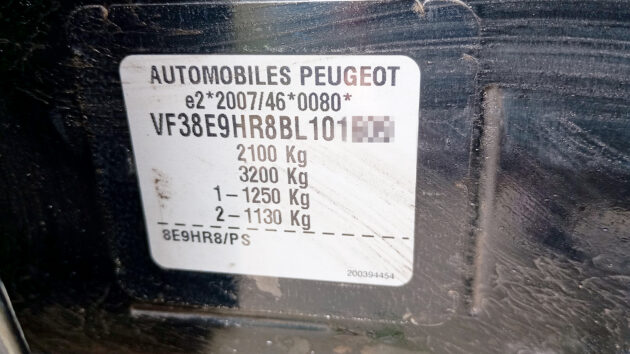

VIN plate check

The VIN plate is usually found under the car bonnet or on a door pillar – either an alloy plate or a sticker. In this example:

- 2,100kg gross vehicle weight, the maximum allowable mass (MAM) of the vehicle including occupants, fuel and payload.

- 3,200kg gross train weight, the combined maximum allowable mass of the vehicle and trailer.

- 1,250kg & 1,130kg maximum axle loads front and rear respectively.

The manufacturer’s recommended maximum towing capacity for this Peugeot is the gross train weight minus the gross vehicle weight, ie 3,200kg – 2,100kg = 1,100kg.

Four great 21-foot trailer-sailers from David Harding

Red Fox

The Red Fox is roomy, stable and a good deal faster than she looks, thanks to her unballasted, asymmetric bilge boards, which also feature on the big sister the Red Fox Vision.

Red Foxes in Brixham. Photo: David Lewin / Future.

These boats offer the benefit of a greater lift/drag ratio than a normal symmetrical keel, boosting windward performance by virtually eliminating leeway.

What’s more, you don’t have to put up with an intrusive keel box in the middle of the cabin. Because of these underwater weapons, the Red Fox can get away with a substantially chunkier hull than other sporty 20-footers.

Beneteau First 210

Beneteau’s First 210 is higher, heavier and beamier than the Jeanneau Sun Fast 20 and, with a centreplate that swings up beneath the hull, leaves a minimum draught of 2ft 4in. Combined with her fixed twin rudders, this is a boat that’s geared more towards occasional trailer sailing than being dropped in for the weekend. Rigging is more challenging too with a mast length of nearly 30ft.

Jeanneau Sun Fast 20

With a long waterline, healthy spread of sail and modest displacement (780kg), the Jeanneau Sun Fast 20 promises a ‘more than respectable performance.’

The Jeanneau Sun Fast 20 has a long waterline and a healthy spread of sail. Photo: David Harding.

Other attractions include the self-tacking jib and asymmetric spinnaker set on a retractable sportsboat-style bowsprit. With an enormous cockpit and simple outboard bracket, this 21-footer is very much a day-sailer or weekender.

Jaguar 21

Like the Parker 21, the Jaguar 21 is considered ‘near-perfection’ in many people’s eyes with its fully lifting keel which leaves a flush bottom. It’s fast and fun to sail, and designed for easy trailing, launching and recovery. Undoubtedly one of the prettiest little boats around, it’s highly regarded and easier than most 21-footers to rig. However, as with other boats that have their ballast in a vertical lifting keel, it can become rather unstable when fully raised.

The Tideway dinghy: celebrating the classic trailer-sailer

While the 10ft option is easy to row and a delight to sail, Clive hails the 12ft trailer-sailer as one…

Seascape 18: the light fantastic trailer-sailer

Despite her racy appearance, the Seascape 18 is a versatile and well-mannered trailer-sailer – as David Harding reports

Tips for buying a used boat trailer

Tony Davies advises on what to look out for when buying a used boat trailer

What is a lugger? And why they make great trailer-sailers – answered!

Compulsive boat owner Clive Marsh explains why little luggers make perfect trailer-sailers

Want to read more articles like this?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter