Onboard his Albin Ballad 30, Russell Seaton incorporates novel race car technology into a fuel supply and polishing setup into his boat's fuel system.

It’s always a good idea to take a closer look at your boat’s fuel system.

After we bought Noontide, our Albin Ballad 30, in Plymouth in April 2023, we spent the following few weeks day-sailing the 340 miles to her new home on the Medway.

The ‘prevailing’ south-westerly winds never appeared, and we spent much of the 340-mile journey under engine into easterly winds that, on some days, had kicked up a bit of a sea.

Russell Seaton has now installed an electric fuel pump, swirl pot and a primary filter and water separator to keep fuel clean on his Albin Ballad 30. Photo: Russell Seaton.

The leg from Brighton to Eastbourne was particularly bouncy, with green water regularly coming over the foredeck. The Yanmar 2GM20 never missed a beat.

Trouble with the boat’s fuel system

Then, a month or two later, on the return leg of a trip to Burnham-on-Crouch, in very benign conditions, the engine faltered and then came to a stop.

We hoisted sail and, while Sean kept the boat off the sandbanks in the Crouch estuary, I went to look at the engine.

The hiss of air entering the fuel line when I disconnected it from the outlet of the sedimenter was a giveaway – there was clearly a fuel blockage in the supply line.

The end of the fuel hose was inserted into a jerrycan of clean fuel and, after a great deal of awkward manipulation of the manual priming lever on the lift pump, the system was bled, the engine restarted, and we motored back to our Medway mooring without further incident.

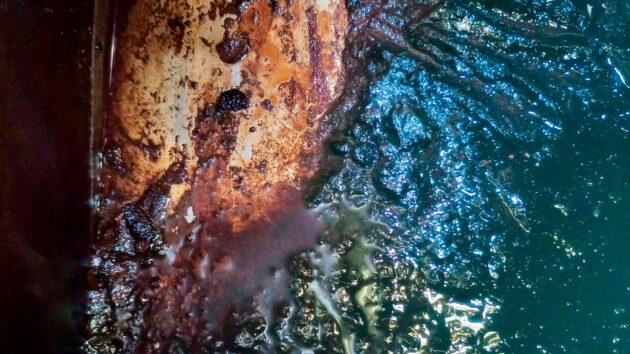

Investigation of the tank and fuel hose showed the culprit to be diesel bug, with a lot of debris at the bottom of the tank and the hose to the sedimenter.

Diesel bug residue in the supply line. Photo: Russell Seaton.

The tank was emptied, removed and cleaned, which was not an easy operation as access is limited to the rather small filler and fuel gauge sender holes.

However, after many hours of scrubbing, steaming (using a wallpaper steamer), pressure washing and drying, the tank was as clean as we could get it, and it was refitted with new hoses.

During this process, the original steel pick-up and return dip tubes in the tank were found to be in poor condition and were replaced with 10mm copper pipe and brass compression fittings – the pick-up even had a pin-hole in it, about half way up, which meant it would have drawn air instead of fuel at low fuel levels!

The old and new dip tubes. Photo: Russell Seaton.

The new dip tubes were installed in the parallel British Standard Pipe (BSP) threads of the tank and sealed using PTFE thread tape, making sure no tape extended beyond the last male thread to minimise the chances of any getting into the boat’s fuel system.

The sedimenter, which was located at a fairly low level behind the engine, and not particularly accessible, was also thoroughly cleaned and refitted.

More trouble

On the next outing, while motor-sailing on port tack, the engine again spluttered to a halt.

This time, the boat’s fuel system was bled, again using the awkward manual priming lever, and the engine restarted. We dropped sail and made our way to the mooring without any further problems.

The 33lt stainless steel fuel tank of the Ballad resides at the bottom of the starboard cockpit locker. It lies against the hull and is relatively wide and flat, with a triangular cross-section. The fuel pick-up is located at the forward inboard end of the tank, where it is deepest.

We surmised that, when motor-sailing on port tack with only a partially full tank, the fuel had sloshed away from the pick-up, and it had drawn in a sufficient quantity of air to stop the engine.

The interconnections were made from copper pipe and fire-resistant marine fuel hose to BS EN ISO 7840. The check valve can be seen in the foreground. Photo: Russell Seaton.

Redesigning the boat’s fuel system

Noontide’s fuel system was very simple, and we suspected original, consisting of a tank, a sedimenter and the engine-mounted fuel filter.

There was no primary filter as such – the sedimenter was only intended to remove large solids and water.

The disassembled sedimenter. Photo: Russell Seaton.

This rather crude fuel system, and the problems encountered, prompted a redesign with three main aims:

- Polish the fuel in the tank to prevent diesel bug from developing

- Make the system tolerant to air ingestion

- Allow easy bleeding of the system

The configuration arrived at is very simple and relatively cheap, but it successfully achieves these aims.

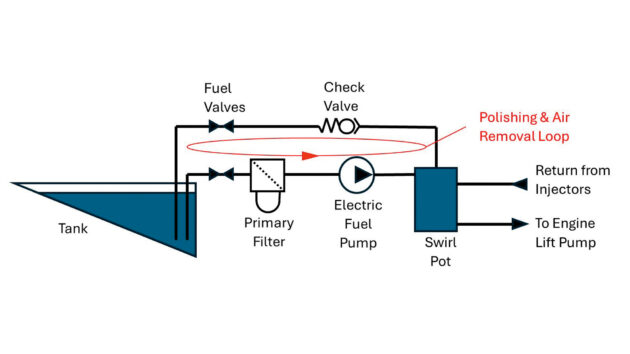

It essentially consists of a primary filter and water separator, an electric fuel pump and a ‘swirl pot’.

The swirl pot is borrowed from the world of motorsport, where cars can suffer from similar fuel starvation issues, but this time generated by high g-forces during cornering or braking, rather than the angle of heel and wave action.

The pump and swirl pot located behind the engine enclosure. Photo: Russell Seaton.

Essentially, a swirl pot is a tallish cylinder with a fuel outlet to the engine at the bottom and a return to the tank at the very top.

A low pressure, but relatively high volume, fuel pump continually circulates fuel via an inlet located at the periphery of the pot towards the top. Any ingested air ‘floats’ to the top of the swirl pot and is circulated back to the tank via the return line.

The inlet is sometimes located at a tangent to the pot so that the fuel swirls within, somewhat like a cyclone, which further aids the air separation process.

The reservoir of fuel in the swirl pot ensures the engine will continue to run until fuel is again picked up from the tank. Unused fuel from the injectors is returned to the swirl pot via a further connection.

The primary fuel filter and water separator are located in the pump suction line such that the circulated fuel is continuously filtered or ‘polished’ to remove contaminants and water.

The bottom of the fuel tank before cleaning. Photo: Russell Seaton.

The electric fuel pump has internal check valves rather than a positive shut-off valve, so the engine lift pump can still draw fuel if the electric pump fails.

A non-return valve incorporated in the return line from the swirl pot ensures that fuel is drawn through the supply line and primary filter rather than bypassing the filter via the return line.

Two fuel shut-off valves are also incorporated in the supply and return lines so that the tank can be isolated if required. These may be particularly useful during filter change-out and bleeding operations.

The fuel filter and valves in the galley locker. The fuel tank is immediately behind, on the other side of the bulkhead. Photo: Russell Seaton.

Components of a boat’s fuel system

All components were sourced from the internet. The filter is a much cheaper copy of the Racor 500 unit, for which the patent has now expired.

While undoubtedly not matching the quality of the original Racor unit in every respect (the T-bar is nickel-plated steel, for instance), I was impressed with the robust construction, which appears entirely adequate, and value for money at around 7% of the cost of a Racor unit.

It is a similar story for the fuel pump, which is comparable to the Facet Posi-Flo automotive unit, with a claimed flow rate of around 100lt/hour and a current consumption of 1.4A.

The unit has a solid-state electrical drive, is claimed to be corrosion resistant, and is provided with a sturdy plastic outer case.

Schematic of installation of the fuel polishing system. Photo: Russell Seaton.

Installation and commissioning

The fuel pump was mounted alongside the swirl pot on a plywood plinth beneath the cockpit sole. This location is close to the fuel tank, on the other side of the longitudinal cockpit locker bulkhead. It was wired to the ‘ignition’ switch so that it circulates fuel whenever the engine is on.

The primary fuel filter was mounted adjacent to the tank on the opposite side of the main transverse bulkhead. It was located as low as possible at the back of a small galley locker next to the engine compartment, where access is easy from the cabin.

The top of the filter is higher than the tank, so it will not overflow if the lid is removed for a filter change without closing the supply shut-off valve.

For convenient access, the shut-off valves in the supply and return lines were also mounted in this locker.

The fuel pump is self-priming, so to commission the system, it was only necessary to turn the ignition key to start the pump, allow the filter and swirl pot to fill, and then bleed the fuel line at the engine-mounted secondary filter and injectors in the normal way.

The original intent was that, by closing the shut-off valve in the return line, operation of the electric fuel pump would force fuel to the engine at around 6psi to facilitate bleeding, as there is no other route available. However, the return line check valve provides sufficient back-pressure to push fuel up to the engine lift pump and through to the bleed points in a gentler fashion, without the need to close the valve or stress the pump.

The electric fuel pump is a reciprocating type, driven by a solenoid coil, and in operation, makes a dull rattling noise.

It was initially mounted directly on an existing upstand from the hull, but when running the pump, noise was amplified by the hull and was unacceptably loud. The noise was significantly reduced by fitting rubber grommets around the mounting bolts on either side of the pump mounting flange.

Dip tubes installed on either side of the fuel gauge sender. Photo: Russell Seaton.

The proof of the pudding

Some may view the use of the primary filter as a polishing filter as a risk due to potential blockage.

However, the continual circulation of fuel through the filter should mean that contaminants build up on the element slowly over time, and are likely to be evidenced by water accumulating in the filter bowl, which should allow a timely filter change.

The filter is suitable for much larger engines and flow rates, so it is hugely oversized for this application.

In the unlikely event that I need to change the primary filter at sea, this can be accomplished very rapidly due to the top-loading design.

It is not even necessary to bleed the filter afterwards, as air entrapment is automatically taken care of by the pump and swirl pot.

Russell Seaton has now installed an electric fuel pump, swirl pot and a primary filter and water separator to keep fuel clean on his Albin Ballad 30. Photo: Russell Seaton.

Bleeding the boat’s fuel system on the engine is now simple.

It’s only necessary to turn the ‘ignition’ key on to activate the electric fuel pump and push fuel up to the engine and through the bleed points. No more fiddling with the awkward lift pump priming lever.

In installations where more pressure is required, or where the check valve does not provide enough back-pressure, closing the valve on the return line should force fuel to the engine.

The result

Fuel tank reinstalled after cleaning (note relatively squat shape). Photo: Russell Seaton.

Since fitting, the system has operated flawlessly for over 100 hours during the 2024 season.

We are much more confident that the fuel is in good condition and that engine cut-outs when motor-sailing are a thing of the past. The swirl pot contains about 2lt of fuel, allowing the engine to run for well over an hour between ‘gulps’ of fuel from the main tank.

When the fuel is low and the boat heeled, the natural movement of a sailing yacht should ensure that fuel sloshes past the pick-up more often than this.

Costs of redesigning your boat’s fuel system

Racor-style filter, £19 (eBay)

Swirl pot £20.49 (Amazon)

Facet-style fuel pump, £14.33 (eBay)

Check valve, £3.51 (eBay)

Shut-off valve £8.65 (pipework suppliers)

Hoses, clips, pipe & fittings, approx £30 (various).

Total: approximately £96.

Russell Seaton is a retired chartered mechanical engineer who has been sailing for about 25 years. He and co-owner Sean McDonald are upgrading Noontide while exploring the East Coast.

The solution to fuel impurity

Engine maintenance is a mainstay of boat ownership but new technology has enabled the average boat owner to spend more…

How can I improve fuel filter efficiency? Ask the experts

Kirk Forrest writes: “I’ve been considering how to improve the fuel filter system on my 45-year-old Fisher 25 motor-sailer which…

Want to read more articles like this?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter