Marine gas engineer Peter Draper explains what’s required for a marine gas system to be safe and legal, and how to assess the condition of the gas system on your boat

Is the gas system on your boat safe, legal and insurable?

Will it satisfy your marine surveyor and insurance company? When was it last tested or inspected, and do you know who installed it?

Usually, that would have been the yard that built your boat, and hopefully, it would have been installed to a high standard.

Apart from routine maintenance and inspections, it should never give cause for concern.

Then there’s the work, rebuilds and alterations done by the skilled amateur. Although uncertified and not strictly legal, their workmanship should not cause any significant issues.

The problem is when work is carried out by enthusiastic, but completely unskilled, have-a-go guys.

New marine-grade regulators have a pressure relief outlet for safety. Credit: Peter Draper

Marine gas systems like these, and those that haven’t been inspected for years, are the ones we should be concerned about.

Those of you with your keels in the fresh water of the inland waterways are bound by the rules of the Boat Safety Scheme and will have regular inspections carried out by a qualified inspector.

As yet, however, there is no such requirement for privately-owned coastal and seagoing vessels, so unless your surveyor or insurance company asks for a gas certificate, your gas safety could be reliant upon poor workmanship carried out years ago.

Before every capable and practical boat-owning engineer emails to shout loudly that working on your own vessel is not illegal, I will refer the interested reader to the Gas Safe website: ‘if you’re going to pay to have gas work done on your boat, make sure the person doing it is qualified,’ and from Gas Regulations, ‘no person shall carry out any work in relation to gas fittings or gas storage vessels unless he (or she) is competent to do so’.

Some may believe that if it’s your own boat and you’re not receiving payment, it’s not illegal, but if you’ve never been trained in gas installation and you’re not registered, how can you or the person doing it on the cheap be competent?

You or they definitely won’t be insured, nor can either of you issue a legally-binding Gas Safety Certificate.

Bad marine gas fittings

Over the years, I’ve seen a rogues’ gallery of incorrect pipe used, corroded pipes in wet bilges, low-pressure hoses on high-pressure systems, water fittings and taps, natural gas fittings, steel hydraulic fittings, hoses out of date by entire decades, gas pipes clipped to engines, bits of car radiator hose and, the worst yet, plastic push-fit pipe used as a marine gas line.

Quite simply, whether it’s fittings, hoses, regulators or valves, if it’s not LPG-approved and marine-grade, it should not be used on your boat.

Take a look at your system. One indicator of a DIY installation is the lack of a test point, which means the system cannot have been tested to the correct standard.

Look for worm drive clips – some are totally unsuitable for LPG pipes – and look for an absence of clipping on copper pipework.

Both shout ‘DIY installation’.

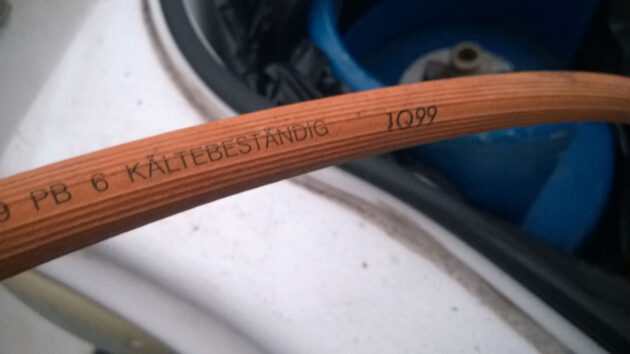

The manufacturing date on this hose is the first quarter of 1999! Credit: Peter Draper

Parallel thread fittings are the worst: soft solder fittings are not allowed. Certain fittings just won’t keep LPG in, no matter how much paste is smeared round the joint.

For other indicators of a poorly-maintained marine gas system, look for long-out-of-date hoses: there will be a date printed or stamped on the hoses, and they should be less than five years old.

Unfortunately, many vessels are fitted with ‘camping’-grade regulators, and may have been so since new.

They are usually blue for butane and red for propane.

They are just not designed for the harsh conditions of the marine environment: they are not marine-grade materials, and don’t have a safety pressure relief valve.

When they corrode internally and externally, they become incapable of regulating the gas pressure.

I’ve found butane regulators rated at 28Mb passing over 40Mb: it doesn’t boil the kettle any faster, and it’s not safe for the eyebrows.

The good and the bad

What’s good and bad about the marine gas we use?

There are two types of gas in common use: butane and propane.

Butane is hotter than propane and is available in a larger range of ‘leisure’-size cylinders, although propane is cheaper the bigger the cylinder you use.

Propane will give you gas when there is thick frost on the ground, whereas butane will stop gassing at the first sign of your breath in the air.

In practical terms, if you use your boat in the warmer months and only have a small gas locker, then you will be on butane: but if (like me) you’re a liveaboard on a converted fishing boat, you will almost certainly be on propane.

Propane is often used by liveaboard sailors

So, the good thing is that there is plenty of choice to suit your needs.

However, what’s bad about butane and propane is that they’re both LPG (liquid petroleum gas) and, as such, are very different from natural gas.

They are produced by the same refining process that makes petrol and diesel, and both burn in the right air/fuel mix.

Most significantly for us on the water, they are both heavier than air, so they will go downwards into the bilges of our watertight boats if there is a gas leak.

Butane is common on board boats

To make sense of that, imagine a bucket of water coloured with blue ink. Tip it over anywhere you have a gas cylinder or gas pipes and fittings: wherever it runs is also where a marine gas leak will find its way into, which unfortunately is the same place as your bilge water and electric bilge pump.

Other unfortunate characteristics are that butane and propane need an awful lot of air to burn efficiently – roughly 30 times their own volume – and if they don’t burn cleanly, they will produce the silent killer, carbon monoxide.

They can also leach through incorrect fittings.

A typical marine gas system

At the heart of a typical marine gas system on a boat, as found on 95% of the vessels I work on, would be a cylinder in a locker which should be gas-tight.

This means that should there be a leak from the cylinder, the marine gas cannot enter the vessel by any means.

From the locker, there should be a drain, preferably straight overboard: there is a relationship between the size of the drain needed to the size of the cylinder stored.

Most lockers are made from the same material as the vessel and are often an integral moulding.

Some have a gas-tight door to access the cylinder, but most allow access from the top only.

There should be some method of securing the cylinders, and the locker should be big enough to contain both the cylinder in use and any spare carried.

This is a new installation, with the regulator fitted directly on the cylinder with an O-clipped hose. Credit: Peter Draper

Don’t, as I have seen more than once, keep the spare cylinder under the guest bunk.

The gas in the cylinder is at a very high pressure in relation to what is required by the appliance (the cooker, in most cases).

A regulator is used to reduce this pressure. The latest marine regulators are now fitted with an over-pressure ‘vent’ to ensure the pressure inside the regulator is not any higher than it can cope with.

Some systems will have the regulator mounted on the side of the locker and a high-pressure hose running from it to the cylinder.

Some have two high-pressure hoses, attached to dual cylinders and selected by a changeover valve.

These hoses are usually black rather than the commonly seen low-pressure orange hose.

The regulator is directly onto the cylinder system will have the low-pressure hose connecting it to the pipework entering the boat.

Bubble testers will show up leaks. Credit: Peter Draper

This hose should be connected with O-clips or swage fittings.

The advantage of the high-pressure system is that there are adaptors available to connect to most cylinders

worldwide, and the twin changeover means not having to swap the regulator to the spare, just moving the valve over.

The downside, as always, is cost. BSS-applicable boats usually have a ‘bubble tester’ after the regulator.

The main pipe through the boat is LPG-grade copper, much thicker than domestic-grade pipework. It should ideally leave the locker higher than the regulator or cylinder and be sealed through the bulkhead.

It should be clipped throughout its run with suitable clips to prevent damage or abrasion. The pipe will usually terminate at a quarter-turn shut-off valve near the appliance, and any moving appliance, such as a gimballed cooker, will have the final connection made via an armoured hose.

Lastly, but most importantly, there should be a test point tee at the appliance.

Rigid copper pipe with suitable clips to prevent damage or abrasion. Credit: Peter Draper

One final variation on this setup is the use of an electronic solenoid to shut off the gas. The idea is that you can leave the gas on at the cylinder and, from a location close to the cooker, turn on the gas via an electronic switch.

They can also be activated via a gas alarm, which will automatically turn off the gas if it detects a leak.

Using your marine gas system safely is common sense: only turn the gas on at the cylinder when you are going to use it, and make turning it off again a matter of habit.

Ensure you have adequate ventilation, which means opening a hatch or portlight.

A quarter-turn shut-off valve. Credit: Peter Draper

Never use the cooker for space heating. If your cooker is old, it won’t necessarily have flame failure devices that shut off the gas if the flame goes out, so never leave it unattended.

Poorly-maintained or even dirty cookers can cause poor burning of LPG. A rusty grill fret/mesh is a very efficient producer of carbon monoxide.

Gas alarms, whether stand-alone or linked to a shut-off solenoid, are a good idea.

The stand-alone ones are by no means expensive, and a practical owner will find them easy to fit: they’re certainly no more complicated than (highly advised) carbon monoxide and smoke alarms.

If you follow the manufacturer’s instructions as to where they should be fitted, they can be put up with a couple of screws each: but remember to test them regularly.

Getting the job done

So, who can legally work on your boat’s gas? It will be someone qualified, registered and insured to do so, which means someone who is Gas Safe registered, someone who has undertaken core LPG gas training and the additional boat qualification.

Ideally, someone who has specific marine insurance and experience working on boats.

Ordinary domestic plumbing and gas insurance will not cover marine work, and the idiosyncrasies of boat gas are very different to LPG in caravans or domestic properties.

Only a qualified and registered engineer can issue the Gas Safety Certificate.

As we know, your BSS inspector can test your gas by the bubble tester, or if they are trained and Gas Safe registered, they can break into the system and use a manometer, which by its very nature is classed as ‘gas work’.

Pressure-testing to regulations. Credit: Peter Draper

Your gas engineer will be able to advise you as to best practice, then install and test the system to the required standards.

They should have the necessary test equipment to pressurise the system to above its working pressure, and should test all pipework and appliances on air and on gas.

They should check all safety devices, flame failure devices, carbon monoxide risks, ventilation and, if relevant, fluing.

Much of the knowledge and equipment required is way beyond the scope of even the most competent and practical owner.

My own electronic manometer will measure down to 00.1 of a millibar: that’s about 0.0015 PSI, or about 1-20,000th of the pressure found in the average car tyre.

So when I sign that the pipework is gas-tight, it is!

Practical-minded boat owners can do a lot themselves. Take a boat that has no gas at all, or which has had to have its substandard gas installation removed: the practical

owner, following a discussion with the gas engineer, could quite capably and legally install the gas locker, drain, cylinder restraint, cooker gimbals, cooker and any ventilation requirements.

Carbon monoxide testing

is of vital importance. Credit: Peter Draper

I would be happy – and it’s my name on the certificate! – for the owner to install the copper pipe run through the boat, providing it was the correct grade of pipe, it was to an agreed route, it was correctly clipped and had no joints.

I, the gas engineer, could then use the correct fittings and procedures and actually connect and test the gas.

That’s going to save the gas man a lot of time and the owner a lot of money.

Is it expensive to use someone like me? Well, once brought up to standard, the ongoing checks and hose changes would cost no more than a three- or four-night stay in a South Coast marina.

A small price to pay for peace of mind, a safe and legal system and that all-important Gas Safety Certificate.

How to detect gas leaks on boats – a handy tool that could save your life

Detecting gas leaks on boats is important, especially as gas standards on boats were very different 40 years ago. Sadly…

Beware using non-marine gas regulators

"This warning has become even more valid after the Calor Gas U-turn as some owners will be swapping back again…

Calor Gas U-turn on phasing out 3.9kg & 4.5kg bottles

Calor Gas has confirmed that it will continue to supply 3.9kg propane and 4.5kg butane cylinders having announced it was…

Calor Gas alternatives for boat owners

With Calor discontinuing some of its gas cylinders, Barry Pickthall looks at the options available for boat owners with older…

Best boat cooker: 10 alternative options for gas-free cooking

Gas cookers used to be the standard choice on almost every boat, but there are good reasons why they are…

Want to read more practical articles like Marine gas system maintenance?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter