Whether you’re new to boating or looking to enhance your navigation with a phone, tablet or MFD, Ali Wood runs through the different chartplotter options

The chartplotter has been a game changer in navigation this past decade, so much so that the UK Hydrographic Office (UKHO) announced its withdrawal of Admiralty paper charts to focus on digital chart products.

After concerns were raised by the Royal Institute of Navigation (RIN), this has been delayed until at least 2030.

“It has now become clear that more time is needed to address the needs of those specific users who do not yet have viable alternatives to paper chart products,” said the UKHO.

Imray also announced it was phasing out its paper charts at the end of the season, although this has now been withdrawn following its collaboration with the Austrian cartographic specialist freytag & berndt (FB) to “ensure the continued availability and development” of Imray’s paper charts and books.

The RIN is currently drafting specifications for electronic charts so leisure boaters can be sure they meet

the required standards.

Garmin’s ActiveCaptain app connects a mobile phone to a multifunction chartplotter display. Photo: Garmin.

Nonetheless, Paul Bryans, chair of the small craft group, believes paper charts will remain an essential navigational aid for years to come. “They will always be a backup independent of external digital information sources and electric power,” he said.

While total reliance on electronics – be that a chartplotter or tablet – is ill-advised, digital charts that you can zoom in and out of on a small screen are already, for many recreational boaters, the main mode of getting from A to B.

New yachts are designed with smaller chart tables, some losing them altogether.

As Peter Chennel says in the book RYA Passage Planning: “Regulatory authorities are coming to conclude that electronic navigation has a place in modern day boating, and we have to accept that electronic charting is now an integral part of recreational boating.”

But we don’t have to just accept it, we can embrace it.

A chartplotter reveals your position far more quickly than any human can hope to achieve with pencil and paper, and there are many features available these days – from AIS to live tidal data – that make life easier and safer so you can spend more time in the cockpit enjoying the sailing.

Photo: Garmin.

Using a chartplotter as a backup

Paper charts and electronic charts can work hand-in-hand.

Many sailors still prefer paper charts for passage planning, where they can enjoy a more ‘zoomed out’ view of the world without having to swap screens, but then on passage a quick look at a chartplotter tells them all they need to know.

For a backup, it’s often enough just to duck below on the hour, and fill in the logbook with the position given on the chartplotter.

Essentially, electronic charts do the same jobs as paper ones. They tell you where you are, give a record of your voyage and provide a means of carrying out calculations to get you where you need to be. Like with a calculator, though, you still need to know how to use one and sense-check your answers.

Also like with a calculator (a scientific one) chartplotters have dozens of other functions you’ve probably never even looked at!

Traditional navigation is an essential part of RYA theory courses. Photo: RYA.

James Stevens, former RYA chief examiner, admits that today’s skippers are ‘decidedly creaky’ when it comes to traditional chartwork.

“Examiners are unimpressed by candidates who can only navigate on a screen and who are unable to update their course and strategy as conditions change,” he warns. “Even on a yacht with all the electronic kit, it’s still important to understand the principles of navigation, not least because it allows you to check that the apparently accurate display is actually telling you the truth.”

So if you’re a complete newbie to electronic charts, but have done your RYA courses and learned traditional navigation, you’re way ahead than most! You’ve done all the hard work already; the push-button/touch-screen bit is easy.

Many sailors, such as the crew of Sweet Dreams in the ARC+ rally, still make a point of using paper charts to confirm their position. Photo: Ali Wood.

Before investing in an expensive chartplotter, though, why not download a free-trial navigation app on your tablet, such as Navionics, and have a play around? You may be surprised at how comfortable it is.

Who produces the digital charts in your chartplotter?

Electronic, or digital, charts are produced by many different organisations.

While UKHO ones for commercial shipping have to meet IMO (International Maritime Organization) standards, there is currently no regulation for leisure boat charts, meaning providers can use their own colour palettes and symbols. This is something the UKHO promises to address before it withdraws its paper charts.

There will always be a place for paper charts. Photo: Ali Wood.

Raster charts

It’s worth remembering that the starting point for the production of any electronic chart is likely to be its paper counterpart, with the very basic elements dating back to the age of lead-line surveys. With a paper chart, when you need more detail – for example, when entering a harbour – you switch to a larger scale chart.

Similarly, the electronic replicas in your chartplotter– whether vector or raster – also have their challenges when it comes to scaling, or ‘zooming in’.

Raster is not a perfect copy but a raster image made of pixels, which show up when you zoom in. To store information about the position and colour of every pixel requires significant data, even after being electronically compressed.

While a raster chart can be magnified until its pixels break down, you can’t zoom in to reveal more detail; instead, either you or the software needs to bring up the next scale chart.

For leisure boaters, there’s a level of information stripped out from Hydrographic Office raster charts to make them more friendly for the average sailor.

For example, wrecks over 30m deep won’t show up on the chartplotter as they’re not relevant, but light characteristics will always be shown, regardless of the level of zoom, as will things like sandbanks.

Vector charts

Most electronic charts are the more ‘intelligent’ vector format.

Raymarine Element7 S MFD features a quad-core processor. Photo: Raymarine.

These use a different system whereby instead of breaking up lines into pixels, they’re stored as segments, and navigation marks can be saved as single chunks of data, rather than pixels. This means an alarm can be sounded, for example, if you enter a shallow patch.

Vector charts are stitched together so there’s generally no need to choose a specific chart, beyond inserting the appropriate SD card into your chartplotter or buying the correct region. The chart is therefore almost always carrying far, far more information than it can show at any one time.

To tackle this, vector charts are grouped in layers so when you zoom out for a broader view, the software can hide the layers beneath, reinstating them when you zoom in. As detail is ‘layered out’ vital dangers may disappear, and a common mistake is to forget to zoom back in to spot these navigational hazards.

Clear sailing displays on a B&G Vulcan 7R. Photo: B&G.

This famously happened in 2014 to Volvo Ocean Race yacht Team Vestas Wind, which struck a reef that the navigator had not seen on his C-Map vector chart. Yet it was a reef so huge that it showed up even on the massive-scale UKHO paper chart for the northern Indian Ocean.

When interviewed, skipper Chris Nicholson said: “We knew about some seamounts, two days off, and the mistake made was that we didn’t zoom in on the depth of the seamounts enough to know that they were more than just seamounts. The information we had was that it was still 40m of depth. Obviously, it wasn’t. It was 3m above sea level.”

Regularly zooming in and changing scale is good practice to view small details and the ‘big picture’ – or indeed, keep a large-scale paper chart handy for the big picture, and use the zoomed-in chartplotter screen for the small details.

How to view electronic charts

While there are huge differences between electronic charting systems, most have GPS technology and fall into two categories: hardware plotters, ie ‘chartplotters’, which operate on bespoke marine instruments such as those by Simrad, B&G and Raymarine, and software plotters or ‘navigation apps’, which display charts on your desktop or handheld device.

While chartplotters use a microSD card, navigation apps for a mobile device can be downloaded from Google Play or the App Store. Often the two work hand-in-hand; you can download charts to your mobile device and transfer them via Bluetooth to your hardware chartplotter.

Chartplotters and MFDs

Chartplotters are available as standalone units or fish finder combos. There are also handheld models, such as Garmin’s GPSMAP 79s. However, most on the market these days are part of a marine multifunction display (MFD), whereby the same screen interacts with other systems such as radar, AIS, sonar, fish finders, weather and autopilot.

Our Raymarine Element S7 did everything we wanted it to on the PBO Project Boat. Photo: Ali Wood.

You’re probably familiar with terms such as estimated position (EP), speed over ground (SOG) and course over ground (COG), but there’s a whole new load of jargon to learn when it comes to MFDs (mostly two words stuck together by a proper noun). Don’t be daunted – just take a look at our glossary (page 35) and you’ll see they’re straightforward.

You can place a single or multiple MFDs indoors or outdoors, and it will be able to connect to the internet via ethernet (cables) and wifi for downloading updates and synchronising data.

In addition to this, by connecting via NMEA to other onboard electronics which record wind speed and direction, boat speed, and more, you enable sailing features such as laylines which help you to choose the best tack or gybe.

However, blindly allowing your electronic charts to guide your autopilot could be disastrous, as PBO contributor Duncan Kent found when he once tested this functionality.

“Yes, the routes avoided dangerous shallows but they ignored tides, winds, overfalls, gunnery ranges and a plethora of essential local knowledge,” he said.

“There’s no way I would have let it take control of the autopilot. Bang through the middle of Portland Bill overfalls without knowledge of tide or wind? No thanks!”

The Raymarine AxiomXL can display a huge range of information including live FLIR camera and augmented reality footage. Photo: Raymarine.

The benefit of having all your data in one MFD is that functions can either be overlaid, swapped, or viewed in a split-screen format. So, for example, you can follow a route, while knowing what the wind and tide are doing, and on the other half of the screen keep an eye on radar or sonar.

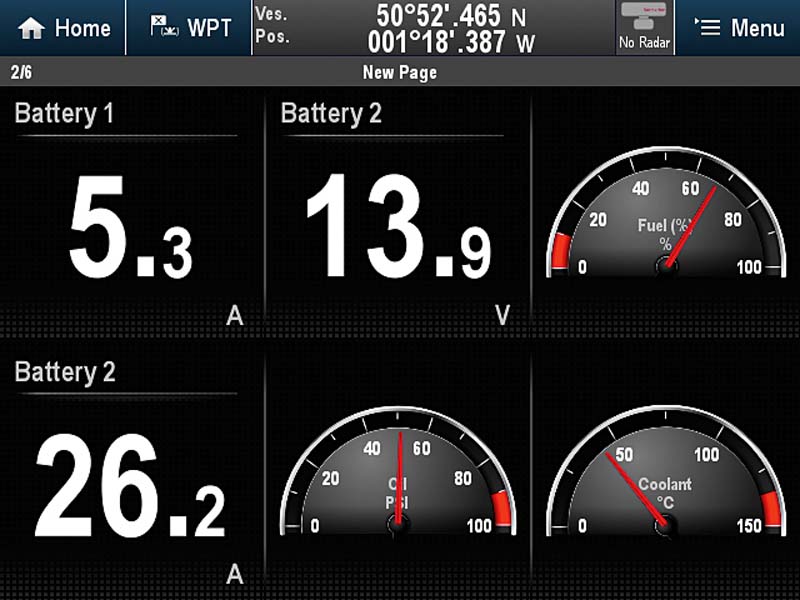

There are many other sophisticated functions performed by MFDs such as entertainment, security and battery monitoring, thermal imaging and live video footage from drones and cameras.

An MFD is usually supplied as an individual unit with accessories such as a sun cover and bracket, and may perform out of the box as a standalone navigator (many have integrated GPS receivers) and as a fish finder/depth sounder if connected to a suitable transducer.

To add further layers, however, you need to integrate other compatible equipment such as radar, autopilot, VHF, satellite antenna if necessary and other items. While installing an MFD is within the capabilities of practical boat owners, for the warranty and assistance you may have to have it installed by a professional.

Apps and integrations for chartplotters

Garmin’s GPSMAP 79s

If you’re thinking of getting a chartplotter for the first time, it’s worth taking time to understand the hardware. If it’s part of a MFD, and requires the frequent swapping of screens, this can feel a bit like having too many windows open on your computer, so if that’s going to fluster you, opt for the largest screen within your budget.

As you move up through the range of chartplotter or MFD options you get enhanced connectivity, processing power, screen sizes and other features, depending on what apps and integrations are available.

For example, a high-end Raymarine MFD might allow you to control lighting, audio and entertainment, while a B&G one can offer race tactics based on tide and wind. New apps are brought out frequently, and don’t necessarily mean you have to upgrade your unit.

Boat shows provide a great opportunity to try out working models. Chandleries and manufacturers may have showrooms with working equipment – Raymarine offers a day’s course to new customers for £150. Even if you intend to stick to a budget, it’s always worth looking at the range to understand what features you could expect if you pay more or less.

Note that when you’re upgrading your electronics to include an MFD, particularly on old boats, you may also have to budget for extras such as the NMEA cabling and transducers.

Digital charts such as those by MemoryMap can be displayed on your plotter. Photo: Ali Wood.

If you’re upgrading from an old chartplotter to a MFD, you’ll see huge improvements.

PBO digital editor Toby Heppell points out: “Screens are now much brighter, easier to see at angles, less troubled by glare and touchscreens are much more responsive when wet too.

The bonus here is that a pure touchscreen will offer increased screen real estate for its mounting size. Simply put, a 7in touchscreen will always offer more screen space than a 7in unit which includes buttons round the outside. But buttons may be something you want as a backup if you are considering going far offshore.”

If you’ve researched computers in the past, you’ll probably be familiar with dual versus quad-core processors. Some MFDs these days are boasting ‘octo-core’ processors, and most will at least offer ‘quad-core’. More cores in a processor basically means the unit’s ‘brain’ can handle more tasks simultaneously, leading to better performance.

Of course, the higher spec your MFD is, the more power it will draw. However, advances in power management and solar, for example, mean today’s cruiser can go longer without needing the engine to charge batteries.

“Needing masses of battery power for your electronics is a bit of a myth these days,” says Richard Marsden of Raymarine. “Normally most of the power comes down to screen brightness; if you’ve got it packed right up, for example, but actually 12in screens can draw as little as 1.5A per hour.”

NMEA 2000

Gone are the various bits of individual kit showing charts, GPS, radar and AIS on separate screens. However, to support an MFD (several instruments on one screen) you need the right interface.

NMEA is a common language invented by the National Marine Electronics Association (NMEA) which allows one manufacturer’s product to talk to another. The latest version, NMEA 2000, allows digital signals to go in two directions simultaneously, with the result that each onboard device can talk to as many as 50 other devices.

The way this works is through a backbone cable running the length of the boat, with individual devices connected via spur cables. The backbone carries both data and power to attached devices. This reduces the complexity of the installation and means far fewer cables than the previous version NMEA 0183.

Under the NMEA standard, manufacturers can use the cable and connector design of their choice as long as it meets certain criteria. So, for example, you could opt for Raymarine’s SeaTalk 2, STng, Simrad Simnet and Furuno CAN – all rebranded versions of NMEA 2000.

A Garmin GPS 128 12-channel marine navigator was an early form of MFD. Photo: Ali Wood.

What about phones and tablets?

The much cheaper alternative to a built-in chartplotter or MFD is to use a navigation app on your phone or tablet.

With the right wireless capability, mobile devices can control all sorts of complex systems, from a chartplotter to a fish finder, radar, autopilot and even engine. However, what they can’t do is withstand marine conditions.

If you’ve ever got your phone wet, or left it too long in hot sunshine, you’ll know how quickly it malfunctions. MFDs on the other hand are built to last.

Besides the need for constant charging, the other limitation to mobile devices is the GPS. It’s not possible to tell from a product spec whether a smartphone or tablet GPS will work offline, and if it does, whether it’s any good. This is because the location system in smartphones combines GPS with triangulation from cellphone towers, wifi, and tracking from your last known position.

There are plenty of places you can sail within mobile phone range, but once you’re outside of these, with no assisted GPS system, you could find it takes from 15 minutes to forever to get that first fix. In other words, don’t rely solely on your smart device.

The RYA advises students not to rely on any one method of fixing, and to constantly cross-check position by another technique.

There are many charting apps available on Google Play and the Apple App Store, some of which are free, with options to upgrade to a subscription for additional features.

Navionics

Navionics (known as Navimaps in the UK) is a popular app for leisure boaters. The company was founded in Italy, 1984, and was the first to produce an electronic chart, which it did on the Geonav chartplotter. Since then, it’s developed a huge database of charts, plus boating apps that offer crowdsourced nautical data from around the world.

When Garmin acquired Navionics in 2017 the cartography teams were combined and the vast database of inland and coastal charts was integrated into Garmin’s own chartplotter and cartography products.

In addition to Garmin devices, Navionics charts also work with third party plotters so you can still plan a route either on a tablet or a phone, and then sync it to your onboard plotter via the Navionics Boating app, or download Navionics charts to an SD card and insert it into your chartplotter.

Navionics also has its ActiveCaptain App (see glossary), allowing your mobile device to talk to your MFD, so you can update charts and route-plan at home, and then transfer the data via Bluetooth to your chartplotter once you’re on board.

Using a ruggedised tablet as a chartplotter

A ruggedised tablet might be a more sensible option on board than a vulnerable standard one. Photo: Ali Wood.

If you enjoy all the features of a tablet, but want a unit that’s heat- and water- resistant and daylight viewable there is the Orca’s Display 2, an Android tablet. The separate Orca Core plugs into NMEA and can send data wirelessly to Orca Display 2, your phone or smart watch.

With the Orca app subscription, you can combine charts with radar, AIS, weather and more features, while still being able to use it like a tablet.

Yachting Monthly’s Sam Fortescue tested it, finding it “fantastically capable, with an attractive and intuitive user interface.” He also liked the “flexibility and portability” of the display.

Which navigation app?

Round-the-world sailor Saša Fegić points out that we all carry smartphones and tablets, so it makes sense to put them to good use on the water.

However, it’s become increasingly difficult to navigate your way between thousands of apps of questionable quality.

“Navionics is probably the best navigation app out there,” he says. “It has the same feel as using an onboard GPS. It provides detailed charts, information about harbours and anchorages, tides, aerial photos and useful user comments. The user can also navigate point-to-point based on the boat’s draught.”

The owner of Rubicon 3 Adventure, sailor Bruce Jacobs notes that many charting apps have been designed with the motorboater in mind, and are focussed on day trips under engine or fishing. Sailors require other essential information such as wind and tide.

“The absolute number one benefit of an app is the ability to instantly see where you are, on up-to-date charts, without the cost and immobility of an MFD. We want charts that show sensible levels of detail as we zoom in and out and, critically, will warn us when we need to zoom in more to see dangers that might have been hidden by vector charts,” says Bruce.

“We then want all the other essential information such as wind and current to be instantly accessible, overlaid on the chart, and we want to be able to quickly measure distance and bearing to a relevant point.”

PBO’s Rupert Holmes lists SailGrib WR as his favourite app for routing and charting, at a one-off fee of £84.

“I used it for well over 2,000 miles of sailing last year, including deliveries between the Atlantic coast of France and the Solent,” he said.

No app delivers it all, but some apps offer additional features, such as internet AIS, which requires payment to unlock.

Whatever app you use, caution is required. Sailors report of depths changing from metres to feet, or ‘minimum depth’ filters being contravened. Sometimes the accuracy is out – showing your boat on land, when it’s clearly entering the harbour, and key data may be removed too early when zooming out of vector charts.

MFD questions to ask yourself

- Is the MFD intuitive?

- Does it have all the functions I need right now and in the future?

- Do I have space for one or more MFDs at my boat’s driving position/s?

- Is the screen size big and bright enough for me to read while the boat is moving?

- Can I show the key features I need in one place simultaneously, such as the chart, radar and sonar?

- What’s my primary use? For example, if fishing, do I need advanced charts to show the shape of the sea bed, or if racing, would I benefit from laylines?

- How easily will it integrate with my other marine electronics such as radar, autopilot, DSC-VHF, AIS, GPS, sonar, engines and level sensors for fuel and water.

- Do I want to use it in conjunction with apps on my smartphone for ease of use?

DIY chartplotter for £200: how to build one at home

John Calton builds his own 10in touchscreen DIY chartplotter with GPS and AIS for a fraction of the cost of…

Best chartplotters: new MFDs that every boat owner should consider

One of the best ways to choose new marine electronics is to get your hands on kit from a range…

What chartplotters can do that your smartphone can’t

A few years ago I felt there was a risk that marine electronics manufacturers would find it impossible to compete…

How to convert analogue engine data and battery levels to show on your chartplotter

Just about every engine installed in a yacht or power boat has some degree of instrumentation, ranging from the basic…

Want to read more articles like this feature on chartplotters?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter