17 years after kick-starting a revolution in trailer-sailing, Swallow Yachts has launched the BayCruiser 21. The new model is light, fast, simple to launch and easy to sail, says David Harding.

The new BayCruiser 21: Is this the best trailer-sailer ever built?

Read what David Harding has to say about the newly-launched BayCruiser 21:

When the BayRaider was launched back in 2008, she heralded a quiet revolution in the world of trailer-sailing.

Small, trailable boats with a twist (or more) of tradition were nothing new, from modern interpretations of traditional designs such as the Cornish Crabbers to others that borrowed from the past, like the Drascombes. Then there were alternatives that you could buy in kit form or as plans, from Fyne Boat Kits for example.

Swallow Boats – as the company then was, before the name changed to Swallow Yachts – offered something different with the BayRaider. In a way she was like a Drascombe Longboat on steroids: lighter and faster, thanks to a highly efficient hull shape, a good spread of sail and a NACA-profile centreboard for a start.

Ready to launch. Even on this shallow slipway, this is as far as you need to go with the trailer. Photo: David Harding.

Her light weight was due to a combination of relatively high-tech construction and, significantly, the use of water ballast.

In unballasted form she could be sailed like a big, stable dinghy or, if you opened the bung to let several hundred pounds of water into the tank in the bottom of the hull, she became self-righting from over 100°.

When I tested the BayRaider in 2008 we sailed in a good breeze with the ballast tank full to start with.

Then, in a squall, we bore away on to a broad reach and opened the self-bailer in the tank to let the water out. As it drained, we hopped up on the plane and ultimately peaked at 11 knots despite reaching the other side of the harbour before the tank was empty.

semi-open transom makes for easy boarding from a dinghy or the water. Note the mainsheet bridle, which could be made wider to optimise sail trim. Photo: David Harding.

To me, the concept made perfect sense. Here was a boat that combined excellent performance with high stability when you wanted it, together with easy trailing and launching because you weren’t lugging fixed ballast around.

Add a touch of traditional appeal – the gunter rig, the attractive sheerline, the wooden gunwale, rubbing strake and bowsprit, the forward rake to the transom – and the package was complete.

Continued evolution

After the BayRaider came the BayCruiser 20, with a higher-volume hull and a substantial, fully-fitted cabin.

The BayCruiser 23 came next, and then the BayRaider Expedition, which was essentially the BayRaider with a one-piece carbon mast and a two-berth ‘camping cabin’.

A vast amount of space in the BayCruiser 21’s cockpit, especially without the mizzen or aft deck of the BayRaider Expedition. There’s room for two or three people on the windward side. Photo: David Harding.

Known to her friends as the BRe, she evolved over the years and became the most popular model in the Swallow range, being followed by the BayCruiser 26 and the Coast 250 power-sailer.

Finally, after 12 successful years with the BRe, Swallow Yachts’ Matt Newland decided it was time for an updated version.

He naturally wanted to retain all the best qualities and improve the others. That meant starting with a new hull for lots of reasons, among them that it would never do for the new boat to be out-sailed by – or merely to keep up with – her predecessor.

The 21 is 8in (20cm) longer on the waterline for the same overall length (she’s called the BayCruiser 21 to distinguish her from the older BayCruiser 20). You’d expect to see a more vertical stem on a newer boat, so that’s no surprise.

Perhaps the most obvious difference, however, is that she’s not rigged as a yawl.

The boom, sail and gooseneck all stay together in a cassette system, on a length of track that clips to the mast. Photo: David Harding.

The BayRaider and BRe both had a mizzen and a bowsprit, spreading the sail area fore-and-aft while keeping its centre of effort low, as has long been common practice among the more traditional style of trailer-sailer and with shallow-draught working boats.

The BayCruiser 21’s yawl rig

As I commented in my tests of the BayRaider and BRe, I have a lot of time for the yawl rig (and not just because we had a Devon Yawl among our family boats when I was growing up).

I thought the mizzen made a lot of sense on a boat like the BRe, where its versatility would outweigh the relatively small compromise in performance. At the same time, I understand exactly why Matt decided to abandon it with the BayCruiser21. It adds cost and complexity and, most of the time, it will detract from the speed.

What I hadn’t fully appreciated is that the yawl is not understood in large swathes of Continental Europe, where many of Swallow Yachts’ owners come from, so Matt had to spend a lot of time explaining it.

Forward is a hatch, recessed foredeck, anchor locker and retractable bowsprit for the asymmetric spinnaker. Photo: David Harding.

Given everything, it seemed sensible to stick to a straightforward sloop rig this time. The jib is tacked directly to the stemhead – no fixed bowsprit – and the mast is taller to maintain a similar sail area (actually slightly greater).

As on the BRe, it’s a carbon mast rather than aluminium, to make it as light as possible to raise and lower and to minimise heel and pitching.

It’s also sealed to provide buoyancy, which would help if you were sailing with the ballast tank empty and managed to capsize. If that were to happen, the companionway and outboard would both stay well clear of the water and you’d just hop over onto the centreboard, as on a dinghy.

It’s good to see that the extra mast length still doesn’t call for spreaders. Again, that saves cost and complexity and makes trailer-sailing so much easier. The fact that the shrouds are in 5mm Dyneema rather than 1×19 wire makes life easier as well: you don’t need to worry about kinking, and you can take turns around a cleat if you need to.

Absence of spreaders simplifies rigging and trailing. Photo: David Harding.

Bigger and faster

Plenty more changes differentiate the BayCruiser21 from the BRe. She has a greater beam (by 12cm/5in), more freeboard and a higher sole in the cockpit to make it fully self-draining, together with higher cockpit seats for better forward visibility.

Despite all this, she’s only marginally heavier. The bulkhead between the cabin and the cockpit has been moved aft, creating a longer cabin while still providing more than ample space in the cockpit (it’s 2.92m/9ft 7in long).

At the other end of the boat is an anchor well and a retractable bowsprit for flying an asymmetric spinnaker.

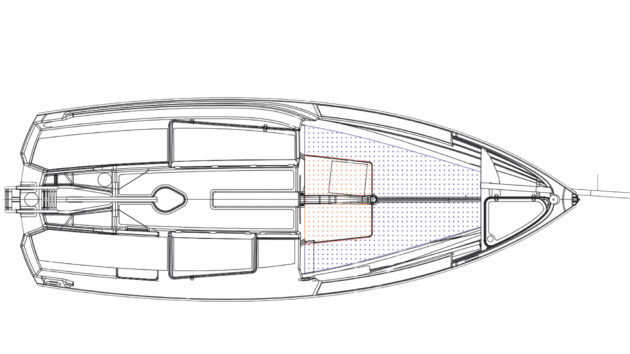

In the cabin, the extra beam, freeboard and bow-to-bulkhead length have created more space. So too has the redistribution of the water ballast to remove the section of tank below the sole on either side of the centreline between the companionway and the compression post.

A vast amount of space in the BayCruiser 21’s cockpit, especially without the mizzen or aft deck of the BayRaider Expedition. There’s room for two or three people on the windward side. Photo: David Harding.

That’s exactly where you land when you step down into the cabin, and it means that you now have a shallow foot-well, whereas on the BRe the sole and the bunk were at the same level.

Moving the water ballast has lowered the centre of gravity and created extra space for propulsion and/or house batteries as a bonus, so gaining the foot-well has not involved compromises elsewhere.

All these changes combine to create a boat that’s roomier, more comfortable and, indeed, faster (as has been demonstrated when the old and the new have sailed together). The comparisons with the BRe might not help you if you’re unfamiliar with the BRe, but in a way that doesn’t matter because, fundamentally, they have just made a good boat better.

If you’re new to the BayCruiser range, and are looking at these boats because they offer what you want, you can decide whether you would prefer to buy a BRe (still in the range, for now at least) or a BayCruiser 21. Significantly, a number of BRe owners have already moved to BayCruiser 21s, so the upgrade seems to have struck a chord among existing devotees.

arge locker to port, with provision for a camping cooker sheltered under the sprayhood. Photo: David Harding.

Ups and downs of the BayCruiser 21

When I arrived at the Swallow yard for our test, the demonstration boat was rigged and on her trailer. Because of the neap tides and insufficient water to launch from the yard’s slipway, we had to trail her along the road to a deeper slipway a few hundred yards down the estuary.

That meant lowering and stowing the mast, which Matt did on his own in about three minutes before reversing the process only moments later.

Among many neat features that simplify rigging and de-rigging is the cassette system for the boom, developed on the BayCruiser 26.

Neat and simple finish in the two-berth cabin, which now features a foot well for more comfortable seating. Photo: David Harding.

The sail, boom, gooseneck and luff slides all stay together, attached to a short length of track that attaches to the mast and butts up to the bottom of the full-length external track. The lazyjacks stay in place, supporting the weight of the boom and sail while you’re attaching or disconnecting them.

Rig tension is achieved through the jib halyard, with the help of a Barton winch on the port side of the coachroof. There are no bottlescrews on the shrouds – just lashings, which are lighter and simpler.

Once you’re ready to launch (15 to 20 minutes from arrival at the slipway shouldn’t be too ambitious, even if you had everything secured for a long drive), you won’t need to get the trailer’s hubs wet on most slipways. The boat slides off easily and then floats in only a few inches of water.

After we launched, Matt sailed single-handed in the mouth of the river while I took the photos. Then I hopped aboard and we headed around the spit, across the bar and into Cardigan Bay.

Aft to starboard is space for batteries, electronics and electrical systems. Photo: David Harding.

In a shifty wind gusting to around 17 knots, Matt suggested that many owners might have chosen to sail in ballasted mode. We sailed unballasted, because it’s faster and more fun, and the boat is still remarkably stable and undemanding.

Besides, even if you were to end up putting the mast in the water, it wouldn’t be the end of the world.

With plenty of west in the wind, the water in the bay was far from flat and on occasions we encountered a succession of short, sharp, speed-sapping waves that would make us slam unless we paid attention, saw them coming and bore away to steer around them.

That’s all part of sailing a relatively small, light boat in that sort of seaway, but the BayCruiser 21 coped remarkably well and skipped along adroitly in the smoother patches.

With no spreaders you have limited control over mast bend to power the rig up and down. She’s not a boat for inveterate rig-tweakers. Her performance-to-complexity ratio is extremely good nonetheless: she’s quick and efficient, yet extremely simple to rig, launch and sail.

You can still play with luff, outhaul and kicker tension as well as the mainsheet.

On the BayCruiser21, the sheet is taken from a narrow bridle on the transom, along the boom and down to a swivel jammer on the aft end of the centreboard case in the cockpit. If you were keen, it would be easy to rig up a full-width bridle for greater control over the mainsail’s twist and sheeting angle.

The outboard hinges up in a well beneath the tiller, with fairing strips filling the aperture in the hull to minimise drag. Photo: David Harding.

After our upwind stint – and while keeping an eye on the time as the tide had started to ebb – we bore away, hoisted the asymmetric spinnaker (tacked to the retractable bowsprit), sailed a few yards and then gybed to head back on a starboard reach.

In those sort of winds, I was unsure whether we would be able to sail high enough to lay the channel around the end of the bar; I thought we might have to drop the kite and reach up under white sails, but the boat held on remarkably well.

Stable surfing

I sailed as high as possible in the lulls, bringing the apparent wind to around 60°, and bore away in the gusts, dumping the mainsheet as necessary. We maintained an easy 6.5-7 knots most of the time, surfing occasionally on the short waves – they weren’t really long enough for proper surfing – at up to 8 knots.

We never felt remotely close to the edge and the helm stayed light the whole time. De-powering the main was principally because you’re not going to gain any speed once the boat heels beyond a certain point: you’re better off sailing flatter and letting the spinnaker do the work.

Then you can sheet in again when you head up in the next lull. If that sounds too much like dinghy-sailing speak, ignore it (I had been racing a dinghy on a course that included some marginal spinnaker reaches in over 20 knots of wind the previous evening). The point is that the BayCruiser 21 is forgiving and well-mannered even when pushed a little.

If you sail her with a full ballast tank and no spinnaker, you’ll have a very steady ride while still covering the ground at a good lick.

The lightness of the helm was noticeable, and remarkable given that there’s no balance on the blade. If a boat stays this light under pressure, you might expect a touch of lee helm when she’s upright, but that was never apparent.

In short, the BayCruiser 21 did everything that could be expected of her. The centreboard is easy to raise and lower, with an uphaul and downhaul on the top of the case, and the rudder will kick up if it grounds.

We put that to the test when skimming the end of the bar on the way back in. Naturally under sail you tilt the outboard up to keep it clear of the water. As on earlier Swallow boats, flexible plastic strips automatically spring into place to fill the aperture once the leg is clear, leaving a flush bottom to the hull to minimise drag. Even this system has now been improved to simplify maintenance and replacement when necessary.

Refinements elsewhere include the pump-out for the water ballast, making it easier to empty the tank entirely. You can pump it by hand or with the optional electric pump; there’s no longer a self-bailer.

In the cockpit you find a generous locker each side, space for a remote fuel tank (our outboard was a 6hp Yamaha) and built-in provision for a camping cooker at the forward end where it will be under the sprayhood – a neat feature on a boat like this where you’re likely to be doing most of your cooking outside.

Below decks, the cabin is simply but neatly finished, and it feels appreciably more spacious than on the BRe.

The expert verdict on the BayCruiser 21

Photo: Swallow Yachts.

In the 17 years since the BayRaider was launched, the concept of the trad-meets-sporty trailable weekender has been progressively refined with each new Swallow model, all of which I’ve sailed at least once.

The BayCruiser 21 gets it spot on with her clever blend of simplicity, efficiency, stability, habitability, performance and practical design. It would have been nice to have longer for our test, but the Welsh tides meant we had to fit a lot into a short time.

We would barely have got some boats afloat, whereas we managed to de-rig, trail, rig, launch, photograph, sail, recover, de-rig, trail and re-rig in the space of three hours. Not many weekenders would allow you to do that.

Photo: Swallow Yachts.

BayCruiser 21 Specifications:

Hull length: 6.02m (20ft 0in)

LWL: 5.67m (18ft 7in)

Beam: 2.18m (6ft 2in)

Draught – centreboard up: 0.25m (0ft 10in)

– centreboard down: 1.50m (4ft 11in)

Weight (empty): 600kg (1,323lb)

Water ballast 400kg: (882lb)

Sail area (main & jib): 19m2 (205ft2)

Designer & builder: Swallow Yachts

Contact: www.swallowyachts.com

BayCruiser 21 Price (basic boat inc. VAT, ex yard): £36,696.

David Harding has been testing boats for more than 25 years and has sailed over 500 types, from dinghies and dayboats to fast multihulls and offshore cruisers. He’s also a marine photographer and runs his agency, Sailing Scenes. His work regularly appears in the yachting press, including Practical Boat Owner, Yachting Monthly and Yachting World.

Want to read more articles like this?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter