Surveyor Nick Vass examines the different types of skin fittings and seacocks on the market and shares advice on how to maintain them.

Skin fittings and seacocks are some of the most important pieces on board.

Yacht design demands a compromise between form and function, between reducing holes that could sink and perforated topsides that would look ugly.

Discharges fitted to the topsides leave unsightly stains from sinks, rusty, oily, sooty exhausts, rusty anchor chains and limescale from water tank vents.

Yet boats need to have holes through their hulls to allow air and water in and out. It’s best if as many as possible are above the waterline for obvious reasons, but the toilet inlet and engine coolant intakes must be below.

Toilets discharge below the waterline to avoid stinky embarrassment, while speed log and depth sounder transducer would be useless above the waterline.

Any discharge, vent, air intake or drain above the waterline must have a hose or baffle moulding that extends as high as possible above the weather deck.

Draining anchor and gas bottle lockers must be watertight and separate from the inside of the hull to avoid flooding and poisoning. Bilge pump outlet hoses must be kept as short as possible, as a long hose greatly reduces the litres that you can pump per minute, while at the same time, the discharge hose must be formed into a high anti-siphon.

A blackened brass seacock is an indication the boat has suffered a lightning strike – all metal seacocks on board will need to be replaced. Photo: Nick Vass.

Through-hulls, also known as skin fittings, are divided into metallic and non-metallic, and each has its pros and cons, but there is no perfect skin fitting when you factor in cost. Plastic seacocks are close, but they are not as strong as forged dezincification-resistant brass, known as DZR.

I have known several yachts to flood due to broken speed log paddlewheels or depth sounder transducers. You put ‘lift-here’ stickers to show where the hoist driver places the strops to avoid fouling the speed log, but it’s hard to avoid placing strops over plastic seacock skin fittings.

Corrosion, meanwhile, is metal’s downfall. Bronze tends to be used for skin fittings below the waterline, even when cheaper brass seacocks are fitted, because bronze is easier to cast but not so easy to machine.

Any metal skinfitting will be damaged by a lightning strike. This is often found on yachts that have returned from hotter climates, so look for blackening.

Seacock Types

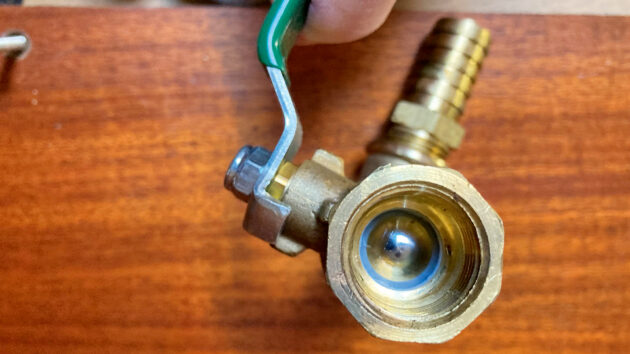

Ball valve

Most modern plastic, stainless steel, DZR and brass seacocks are of the ball-valve type. A ball with a hole through the centre rotates through a round body with PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) seals.

The most common type is nickel-plated brass as found on most new yachts. The brass ball is chrome-plated so that it is smooth and makes a good seal with the PTFE lip.

The problem with these is that the central spindle that runs through the body, ball and handle can break away from the ball.

You won’t know that this has happened as the handle will be easy to turn, but the valve won’t be closing.

Ball valves are the most common type of seacock. Photo: Nick Vass.

Another issue is that limescale and barnacles cover the ball, ripping apart the PTFE seal, making it leak. If you have this type of seacock, then bear in mind that the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard that they are made to stipulates that they should last for five years – after that, you are risking your boat.

My recommendation whenever I see cheapo seacocks is simply to replace them with better ones.

Gate valve

Gate valves are easy to recognise because they have a rotating wheel instead of a 90° handle to open and close them. They are slow to operate because they take a lot of turning.

Generally, older gate valves are made of bronze, and they can look fine from the outside, but the internal components are made of steel, which rusts and seizes up.

A rotating wheel rather than a handle is used to open a gate valve. Photo: Nick Vass.

Cone valve

Traditional Blakes seacocks, as found on many older British yachts, work by rotating a cone with a hole through the middle within a body with two holes in it. You line up the holes to let the water through and turn the handle 90° to close.

They need annual servicing, lapping in the faces with engine valve cutting paste before applying waterproof grease.

That aside, they last for decades and can be serviced without removal from the vessel between the tides, but they can tend to either drip or seize up. Blakes seacocks are still made from DZR brass.

SeaSeal also makes cone valves, but they are made from just one metal to cut out dissimilar metal corrosion, and they are forged to make them stronger.

Plug valve

Many racing yachts have plug valve seacocks that have a flush finish on the outside of the hull. Plug valves can be either metal or plastic. Forespar makes Flowtech flush plastic plug seacocks.

How to check your seacocks

It’s essential to check hose clips for corrosion, especially if they’re made of two dissimilar metals. Photo: Nick Vass.

Turn the handle or wheel. The centre spindle might have parted from the gate or ball if it is too easy to turn. PTFE seals wear out, making the handle easy to rotate, but the valve will be letting water through.

If the handle or wheel is hard to turn, you should replace it. However, you can service stiff Blakes seacocks.

Colour black. The seacock should be replaced if it is black, as it’s probably been struck by lightning or attacked by stray current corrosion.

Colour green or pink. Replace the seacock if green with verdigris, as this means that the outer nickel plating applied to brass seacocks has worn off, exposing copper. Scrape skin fittings with a knife.

Classic verdigris corrosion on a seacock. Photo: Nick Vass.

If bright yellow metal is exposed, it’s probably fine. Replace urgently if the skin fitting or brass seacock is pink, as this means that the zinc content of the alloy has corroded away.

Wiggle. Give the seacock a good tug occasionally. If it falls off in your hand, you will know that it’s time to replace it. Have appropriate bungs ready, though, as your boat will sink!

Leaks. Replace skin fittings that are dripping. However, Blakes seacocks can be serviced. Modern seacocks should always be bone dry externally, but cold metal can cause condensation.

Make sure there are no cracks on the hull around skin fittings and that the hull does not flex at all when the seacock handle is turned. Fit larger backing pads to the skin fitting to spread the load if cracks or flexing are found. SeaSeal supplies backing pads for all types.

Only use reinforced hose and regularly check for signs of perishing or splitting. Photo: Nick Vass.

Check the skin fitting for cracks or bending. I have seen several broken sonar transducers damaged by hoist lifting strops.

Check flexible hoses for signs of perishing and splitting. Always use reinforced hose, never plain PVC and use fire-retardant hose to the coolant intake seacock within the engine space.

Check all hose clips as these are often made of two dissimilar metals. The band might be stainless, but the worm drive could be nickel-plated mild steel.

Prevention and what to do in an emergency

Have cone-shaped softwood bungs close to each skin fitting or opening below the waterline. Have several sizes close by as the internal diameter of the hose tail will be different to the skin fitting or seacock body.

Replace sacrificial anodes on a regular basis. Whenever the boat is ashore, replace anodes even if they have not depleted, as anodes that don’t deplete might be made of the wrong alloy and might not be working, rather than simply not having to work.

Disconnect the shore power lead when you leave the vessel, or at least fit a galvanic isolator, as stray electrical currents and galvanic corrosion kill metal seacocks.

Close all seacocks other than cockpit drains whenever you leave the vessel. Work them or they will seize up with limescale, salt, corrosion or barnacles.

Replace nickel-plated brass skin fittings every five years.

Replace nylon skin fittings that are exposed to sunlight above the waterline every 10 years.

Nylon swimming pool valves are often fitted to ballast water tanks on offshore racing yachts – but if they’re not reinforced with glassfibre, they can be susceptible to cracking. Photo: Nick Vass.

Replace diesel heater exhaust hoses every five years – during surveys, I have found so many of them to be rusty.

Carbon fibre is often found on new spinnaker poles, davits, bowsprits and rudder stocks and tillers, but carbon fibre is a good conductor of electricity and can transfer currents from mast and rigging to the hull skin fittings through copper-rich antifouling submerged in seawater electrolyte, if fibres are exposed.

Antifouling often contains a lot of copper, which is a dissimilar metal to stainless steel and so can react, causing corrosion of metal skin fittings. Always isolate and insulate metal with epoxy and primer before applying antifouling, and never apply copper-rich antifouling to aluminium rudder posts and saildrives.

Seagoing yachts have zinc anodes that protect brass seacocks by wasting away before the seacock corrodes. It is worth noting that Volvo Penta is moving over to aluminium anodes. This is because zinc anodes are made from an alloy which includes cadmium, which is harmful to wildlife. However, by introducing aluminium, you are introducing another dissimilar metal.

Failure to regularly check your skin fittings and seacocks could mean the loss of your yacht. This brass seacock is so badly corroded the owner is lucky it did not fail. Photo: Nick Vass.

Skin fitting and seacock materials

Stainless steel

You would think that stainless steel would be perfect for skin fittings and seacocks, but it can suffer from crevice corrosion, eating away at the metal. Stainless steel diesel heater exhausts rust, allowing lethal carbon monoxide inside the accommodation area of the boat.

Stainless steel is a high alloy ferrous metal, but there are so many different types, all with different properties, so if you do buy stainless steel seacocks, make sure that they are tested and certified by a genuine European or American classification society, such as Lloyd’s Register, for marine use below the waterline.

Don’t trust photocopied compliance documents that often accompany stainless steel products made in places like China, which can be bought online.

Stainless steel needs to passivate on contact with air or oxygenated sea water as the chromium content is exposed, but it will rust when deprived of oxygen in stagnant water. Micro-organisms in slimy bilge juice and tank water consume oxygen, turning the water acidic, which is why boats are not made of stainless steel. They would rot out.

Stainless steel toilet waste holding tanks and engine exhaust water separators tend to rust along the weld seams, leading to flooding with disastrous consequences.

Plastic skin fittings

TruDesign (www.trudesign.nz) glass-reinforced composite nylon seacocks are now approved by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency for use inside engine spaces on commercially used coded sailing school and charter yachts, as they are fire retardant.

TruDesign seacocks are fire retardant so can be used inside engine spaces. Photo: TruDesign.

Forespar (www.forespar.com) makes composite seacocks from Marelon polymer. Ordinary plain white nylon plastic is a sound material for skin fittings above the waterline, but it degrades in sunlight and becomes brittle and chalky. I recommend replacing plastic skin fittings every 10 years, but luckily, they are cheap as chips.

Nylon swimming pool valves are often found on offshore racing yachts to fill and empty the ballast water tanks. Nylon not reinforced with glassfibre can crack apart.

Brass

Brass is cheap, so most new yachts are fitted with brass seacocks. They only last around five years before the brass goes green with verdigris and corrodes.

Brass seacocks have a brass ball that is chrome plated, a stainless steel spindle, a mild steel handle and a nickel-plated brass body – all dissimilar metals. Replace brass seacocks every five years or if they look black, green or even slightly pink. Brass seacocks often corrode from the inside and might look OK externally.

Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, which easily dissolves back into its elements when electrical currents and seawater saline electrolyte are present. Brass has to be plated with nickel, so it might look like stainless steel externally.

Groco seacocks are made from leaded red brass. Photo: Nick Vass.

Bronze

Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin with other metals and minerals, but there are so many types of bronze that categorising is problematic. Admiralty brass is actually a type of bronze as it contains 1% tin.

Interestingly, the American brand Groco (www.groco.net) states that their seacocks are bronze and make a big deal of it, as do Americans in general, who think that Europeans are barmy for having brass seacocks.

Groco seacocks are actually made from C84400 alloy, which is more commonly known as leaded red brass. The lead makes it easier to machine. This alloy contains approximately 79% copper, 8% zinc, 6% lead and 3% tin plus other metals and minerals such as phosphorous, nickel, aluminium, silicon, antimony and sulphur.

DZR

A British company called SeaSeal makes seacocks in their forge in Birmingham. SeaSeal (www.seaseal.co.uk) seacocks are forged rather than cast, making them very strong, and they are made from a near-bronze brass alloy.

Blakes seacocks are also made of DZR. www.blakesandtaylors.co.uk

To make the hull flush, Sadler Yachts used to swap the original Blakes bronze bolts with counter-sunk flush head bolts, introducing a dissimilar metal that caused some to corrode prematurely. When refitting Blakes seacocks, always use the dome-head bronze or DZR bolt supplied by Blakes.

DZR stands for dezincification-resistant brass. This is an alloy of copper, zinc and tin with the addition of arsenic, which greatly reduces the loss of the zinc content from corrosion. The zinc content of DZR is a lot lower than in ordinary brass.

Signs of pink in the metal is an indication of dezincification. Photo: Nick Vass.

Corrosion and erosion

Dissimilar metals cause electrons to move between them when immersed in sea water. Reducing or cutting out dissimilar metals greatly reduces corrosion, which is why single-metal seacocks make sense over ball valves that have a nickel-plated brass body, a chrome-plated brass ball, a stainless steel spindle and a mild steel handle. That’s five metals in one seacock!

Metal seacocks and skin fittings corrode where an element of the alloy is lost due to electron movement. Plastic skin fittings are slightly more susceptible to damage as they are softer, but at least they don’t corrode.

Most modern yachts I survey have corroded seacocks suffering from galvanic action as they’re made of inexpensive nickel-plated brass. My advice is to replace them with better-quality seacocks made of plastic, single metal DZR or bronze.

Nickel-plated brass is susceptible to corrosion. Photo: Nick Vass.

Galvanic corrosion occurs because various metals used in a boat have different electrical potential properties. The different potentials or willingness to give up electrons are measured on what is called a ‘galvanic scale’. Zinc sacrificial anodes are fitted to the vessel because zinc is higher on the galvanic scale and will be eroded well before the zinc content of the brass seacocks.

The metal that gives ‘waste-away’ electrons is called the anode. The metal that receives the electrons is the cathode, but the metals can’t exchange electrons unless an electrolyte, such as seawater, is present. Zinc anodes protect cathodes, such as the seacocks, if they can ‘see’ them through the water. They don’t have to be physically bonded together.

Stray current corrosion is a type of electrolysis where currents in AC and DC electrical systems wander from their intended path due to an electrical fault or short circuit. It tends to be localised and manifests itself where the current leaves via a metal component, such as a skin fitting. Stray current corrosion will make a seacock turn a black colour.

How to replace ageing through-hull fittings

In preparation for an extended voyage, Kerry and Fraser Buchanan replace all below waterline through-hulls with composite fittings

Why is there a film on the seacocks?

PBO reader Camilla Ransom has found a "strange film" on one of the boat's seacocks. What should she do? Surveyor…

Fitting new seacocks and skin fittings on the PBO Project Boat

Maximus, our PBO Project Boat, had four seacock fittings that need changing – three ball valves in the forepeak (1…

Want to read more articles about skin fittings and seacocks?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter