Daria and Alex Blackwell share the close-quarters manoeuvring techniques they’ve picked up at the helm of a 57ft, heavy-displacement classic ketch

We’re just getting ready to spend a little time in marinas, which is always a source of consternation for us. We have a 40-year-old, 57ft classic ketch with no bow thruster, write Daria and Alex Blackwell.

She has a modified fin keel (an almost full keel) and heavy displacement – so in other words, Aleria doesn’t manoeuvre very well in tight spaces.

She is meant to be crossing oceans. That’s one of the reasons we really like to anchor out, but in reality, we’re always going to have to get to a dock for fuel, water or overnighting in the absence of a safe anchorage at some point, so we have had to learn how to use what we have to get ourselves into tight spaces.

Our boat doesn’t do very well in reverse.

Aleria’s rudder is quite small in comparison to the almost full keel. When motoring forward, the wash from the propeller is deflected by the rudder, and she steers well.

In reverse, the wash goes down either side of the keel, and the rudder is quite ineffectual. Any wind that might be present exerts more force than the rudder might.

She does, however, kick out to port quite nicely when we first start reversing. This is due to prop walk.

It means that we can indeed turn our boat in a narrow channel or in a marina.

Here are some points that are useful to know about how it works.

Prop walk

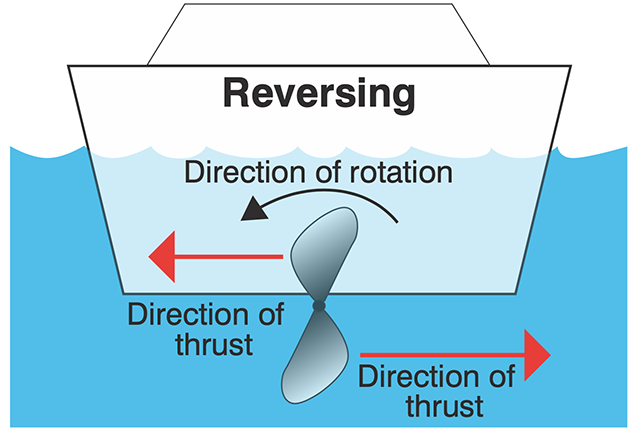

When reversing, the stern tends to kick out to port

With a single-screw boat, you may have noticed that your boat will kick out to one side or the other when reversing, and also initially when moving forward.

This is known as propeller walk, or prop walk.

It is more pronounced when reversing as the rudder is initially less effective, but it also happens when moving forward.

As the propeller turns, the blades move from deeper water to shallower water and then back to deeper water. At the top of its rotation, in the shallow water, the blades provide less propulsion than in the deeper water.

The blade is angled so that the turning propeller will propel the boat forward or in reverse, depending on which way it is turned.

However, in its rotation, the blade will also push out to the sides, with the top pushing one way and the bottom the other way.

The direction of the rotation of the bottom blades determines which direction the stern of the boat will be pushed.

Propeller types

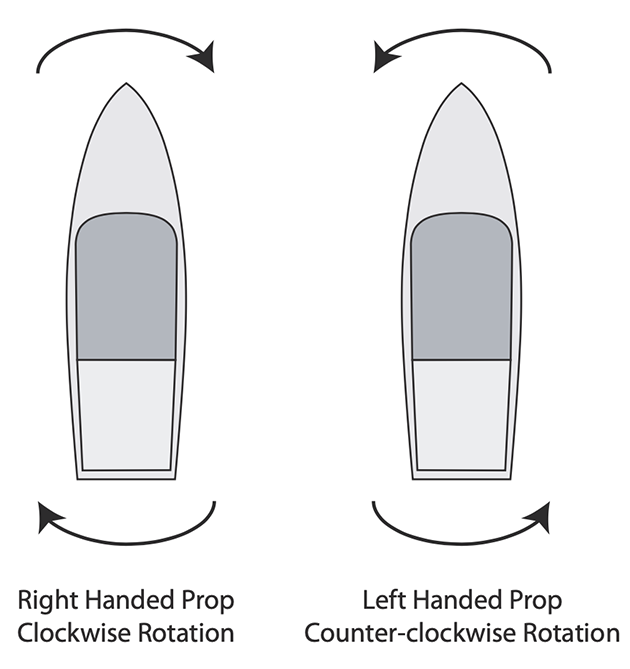

Right-orientated

(right-handed – most common)

If your prop is a right-handed one, when you reverse the prop walk will cause your stern to kick to port and your bow to starboard.

In ahead propulsion with the rudder centred, the prop will rotate clockwise (to the right), causing the stern to walk to the right or to starboard and causing the bow to turn slightly to port or left.

It is more pronounced in reverse than in forward gear.

Most (but not all) single-propeller boats, such as monohull sailboats, have right-handed props.

Left-orientated

(left-handed – quite rare)

Left-handed propellers rotate counter-clockwise to provide forward thrust.

When in reverse, they will kick the stern to starboard, and when in forward, the stern will be pushed to port.

Left-handed propellers are primarily used as one of the pair on twin-engine boats to cancel the steering torque that results if both propellers spin in the same direction.

Left-handed propellers are sometimes used on lobster fishing boats where the wheelhouse is aft and starboard. Kicking to starboard while reversing makes docking easier for these boats.

We have also seen left-handed props on the occasional sailboat.

How to tell which type of propeller you have

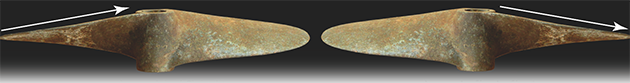

The right-handed prop is pictured left, and the left-handed prop is pictured right. Credit: Daria and Alex Blackwell

To see what type of prop you have, you can stand behind your boat (at the stern) and look at her propeller.

Have someone shift into idle ahead propulsion and note the direction of rotation.

If the propeller rotates to the right in forward propulsion, you have a right-hand propeller.

If it rotates to the left in forward propulsion, you have a left-handed propeller.

There are several other ways to tell if your prop is left- or right-handed.

If you look at your propeller from the side, the leading edge of a right-handed propeller will run from bottom left to top right.

On a left-handed propeller, the leading edge will run from top left to bottom right.

You can also determine which one yours is by holding it in the palm of your hand.

A right-handed prop. Credit: Daria and Alex Blackwell

If your thumb fits comfortably on the blade when held in your right hand, it is a right-hand propeller.

A left-handed prop. Credit: Daria and Alex Blackwell

If your thumb lies comfortably on the blade when held in your left hand, it is a left-handed propeller

Using prop walk to your advantage

Docking

Prop walk is a very useful asset for docking.

If you have a right-handed prop and know your boat kicks to port, then coming into a dock portside-to can make you look like a real pro.

Just come gently alongside with your bow angled towards the dock.

When you are within a couple of feet of the dock, put it into reverse and briefly gun the engine at about half throttle.

Your forward motion should stop and your stern will kick to port, towards the dock.

When done properly, you will have executed a perfect parallel parking manoeuvre.

Your crew will be able to step off the boat to secure the dock lines with ease.

Turning a boat with little room

We were cruising out of Long Island Sound in the US one year when a tropical storm warning was issued.

We decided to take refuge in a marina, but the only available space meant that we had to come in, turn our boat 180° in a narrow channel and then come alongside.

When a boat turns, it is actually the stern of the boat being steered, because the rudder is positioned aft.

When a boat is moving forward, it pivots around a point about a third of the distance from the bow, roughly at the mast.

When turning in tight quarters, therefore, it is important to watch your stern so it doesn’t kick out into an obstruction.

When motoring astern, the pivot point moves to a point one-third of the distance from the stern. Add in prop walk, and these turning characteristics can be compounded.

We went directly into the lagoon and stopped the boat while initiating a turn hard to starboard.

We then put her into reverse and gunned the engine. Her stern kicked out to port, which we knew she did.

We then put it into forward and revved the engine at about half throttle. Her bow swung gently but obediently to starboard.

As soon as she started moving forward, we put her back into reverse, and so on.

Throughout the whole procedure, our position had not changed – just the direction we were facing.

After several reversals, we were facing in the opposite direction, perfectly aligned with the dock.

The proper name for this manoeuvre is ‘back and fill’ – it is also called a ‘pivot turn’.

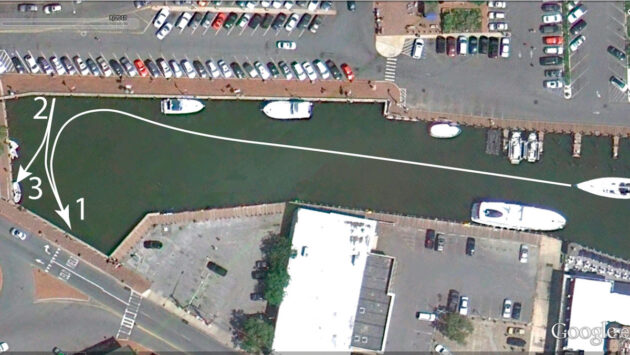

One of the best places to watch how not to do it is Ego Alley in Annapolis, Maryland.

This is a relatively narrow channel that terminates with a turning area at its end.

When arriving in Annapolis, most boats will motor down this channel to see and be seen. We, of course, were no exception and did it also.

Most boats will come down the channel hugging the right side, as in the illustration. They will then turn left into the space provided (1).

Next, they will back down. As they have a right-handed prop, their stern will kick out to port (2) – irrespective of how their helm is set, as the space is tight. They will then go forward, and their boat will initially turn right before the rudder bites (3) – bringing them closer to the end of the channel. If they have a bow thruster, they may save face, but it is undignified to do so. Another reverse and another forward, and they are usually tight up against the wall. The boat hook comes out, and there is much shouting and consternation.

It is quite rare for a boat to come in hugging the left-hand side, as in the second illustration. Once the initial turn has been made (1),

backing down (2) pulls the stern to port, achieving a better angle for an exit. It might take a few back-and-forths to get there, but the end

result (3) is quite easily attained. Practise this manoeuvre in open areas before you get into a confined space, and learn how your boat

reacts under different conditions of wind and current. That way, once you find that you must pivot in a confined space, you will be well

prepared to execute your manoeuvre with confidence.

Reducing the turn radius

Credit: Illustrations Alex Blackwell, © Coastalboating.net

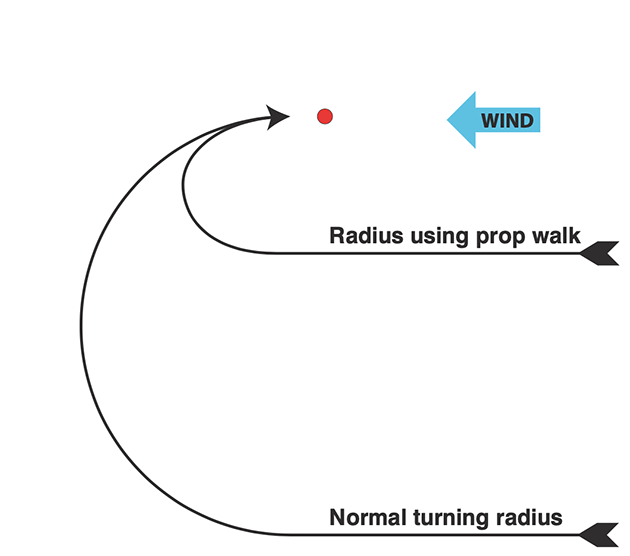

Our boat has a rather wide turn radius.

To pick up our mooring, which is at the confluence of a small inlet and a wider bay, we have to come in, usually with westerly winds behind us, turn around clockwise into the wind and come up on the mooring.

The problem is that her mooring is in a relatively small hole in a wide-open area.

It is quite shallow almost immediately outside the swing radius of her mooring.

To reduce the turning radius, we once again make use of her prop walk.

Any sharp turn is a challenge for our boat, and particularly serious is a sharp turn to port.

Credit: Illustrations Alex Blackwell, © Coastalboating.net

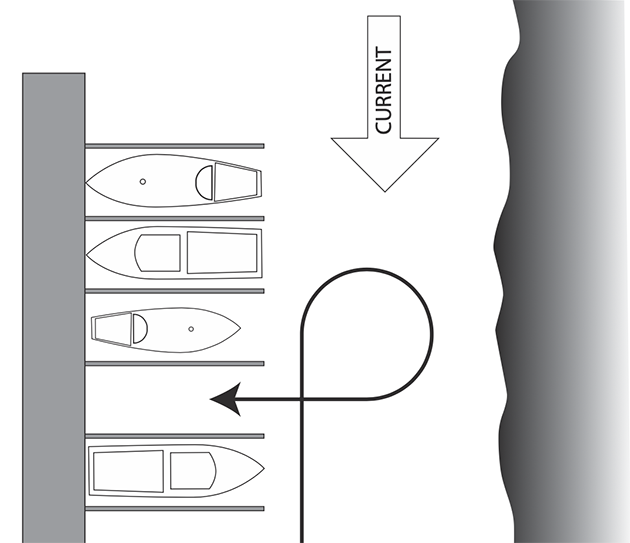

On an occasion where we wanted to get into a slip to port in a narrow channel with a current coming towards us, we opted for a 270° right turn, again using her prop walk.

We started the manoeuvre by overshooting the berth and then initiating the right-hand turn.

At the end of the turn, we were lined up with the up-current finger dock.

A little forward throttle as we were pushed downstream saw us slide right in, to the utter amazement of the dock-hand.

The frightening moment came when we had to reverse hard to avoid overshooting the slip and making a bullseye at the far end.

Suffice it to say, it all worked just fine.

Marina boat manoeuvring: reversing the roles

When couples sail together, one usually takes the lead when it comes to marina boat manoeuvring, remaining on the helm,…

How to make an easy marina mooring pick-up device

Jon Sharp devises an easy marina mooring pick-up using a hoop on a pole

Boat handling tips: marina exit strategies

You want to turn one way to get out of your berth, but both the boat and the wind have…

Boat propeller: How to choose the right one for your boat

The correct prop can have a dramatic effect on your boat's performance. Ali Wood learns how you can save fuel,…

Want to read more seamanship articles like Prop walk: how to use it to your best advantage?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter