Delivery skipper Ben Lowings explains how you can make your yacht handle better with efficient helming, sail trim, and routine upkeep to improve boat performance when cruising.

Expert delivery skipper Ben Lowings offers his top tips to help improve boat performance and handling.

Efficient helming

Sailing starts – and ends – with the human element.

You may have the most streamlined, light and effective rudder that turns your boat on a sixpence, but if your steering is not efficient, then that’ll let you down.

Waggling the rudder around when you’re nearly stationary won’t give you a jot of extra boat performance. The only counter to this is if you’ve totally lost power, you’ve no wind or oars, then flipping the blade from one side to the other will give you a teensy bit of forward motion, in imitation of a sculling oar.

Efficiency here is all about the famed ‘steer, then gear’. On displacement craft of any weight, it’s ‘gear, then steer’ (this is to be taken in advisement, I prefer to think of ‘way on: wheel on’ – you need water flowing over the rudder for the rudder to do anything).

When you have some way on, that is to say, you’ve got water flowing on either side of the rudder blade, then it is worth thinking about efficient helming.

Sailing to windward: how to tweak your sails to improve performance

Some boats need persuasion to make to windward, so tweaking the sails to best advantage can make all the difference.…

The essential tools to keep on your boat

What tools do you really need for a boat? Say you now own a new or new-to-you boat, and you’re…

Where to sit while steering for ideal boat performance

If you have got tiller steering, it is very inefficient to sit with your back aligned with the transom, or at least square to the central axis of the boat. You’ll quickly find it gets very tiring, and has a negative impact on boat performance. There is not a lot of space for your arm to drag or push the tiller bar. You’ll tend to steer away from you, which in a sailing boat means a likelihood you’ll be pushing the boat into the wind.

Make sure you are in the correct position to steer, to ensure your boat cuts through the water as efficiently as possible.

This is because your midriff is stopping you from dragging the tiller bar towards you to the same extent as you could push it in the other direction. It is physically uncomfortable to hold the tiller bar for any length of time in that position; the bar can also press into your stomach or even pin you back if the water grabs the rudder and holds you there.

Efficiency is the name of the game. Hold the tiller at an arm’s length, as a rower would an oar, and move your body.

Sit facing one side of the boat, and move your head to look ahead. Your feet have good holding on the cockpit floor, braced against pitching, and your backside is flat and stable on the cockpit seat.

Holding the tiller at the end of the bar, or even better with an extension that is fixed to this point, maximises your control over the steering.

Out on the water, cruising, it is a general rule of thumb that all your applications of the rudder should be gentle; if you can keep the water ‘sticking’ to the rudder, then you have more turning power.

If you’re snatching or jerking or sweeping the rudder blade, it is relatively inefficient because you’re disturbing the water flow, discarding the opportunity to bend that flow to your advantage.

Yes, you’re shoving the water aside heavily, and the boat will slew round or stop, but the same result can be achieved more efficiently with a smooth movement that takes longer to bring the rudder around in an arc.

In a displacement craft, the turn will always induce a slip. The stern will careen outwards; the boat’s backside will drag off the edge of the turning circle. Putting uniform pressure into your turns will improve your rudder’s performance.

Weight distribution on board can affect your boat performance, too

When it comes to weight distribution, the boat should be flat, fore and aft, as much as possible. Having crew members on the rail adds a ‘righting moment’ when the airflow wants to tip the boat on its side.

Remember: sailing as flat as possible is sailing as fast as possible!

Think about your rigging

Setting up your rig for success will give you greater efficiency.

You can tune parts of your rig yourself, such as tensioning the bottlescrews. Photo: Ben Lowings.

Standing rigging – most notably the shrouds holding up your mast from the sides – is designed to be kept under significant pressure.

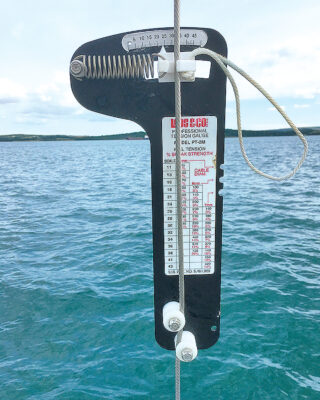

A tension gauge applied to part of the standing rig in question, and moderated by the relevant turnbuckle, in coordination with the manufacturer’s recommendations, is a good sign of the lie of the land.

A professional tension gauge will make rig set-up easier and help maximise boat performance. Photo: Ben Lowings.

Loading on various components of the mast and spreaders, through the shrouds, cap-shrouds and diagonals or side-shrouds is usually best left to professional riggers, unless you really know what you’re doing when it comes to rig tuning.

Lighter running rigging, like thinner halyards made of Dyneema or lighter materials, as well as lubricated blocks, are also worth considering.

Trim your sails right to maximise boat performance

Anything that contributes to the smooth flowing of layers of air closest to the sail will make a boat move more efficiently, so pay attention to sail trim, twist, tuning, sail construction and sail combinations.

Stay on top of sail trim for optimum boat performance. Photo: Peter Cade / Getty.

The correlation between hull shape and boat performance

There’s a strong relationship between the length of your vessel, your hull design, and boat performance, or the speed you can get from your yacht.

Longer and thinner craft tend to dart through the water more quickly.

Wetted surface area is minimised on the French ocean-going trimarans. Often, only one of the three hulls is really in the water. More than a hundred feet of ‘arrow’ will be slicing through (or perhaps mostly ‘over’) the water.

Compare with the smaller types of old ‘cod’s head and mackerel tail’ wooden ship.

They might have a keel of similar length, but hull speed is a lot slower. The vessels were beamier, and the bulbous-shaped ‘cod’s head’ bows seemed to bluff the waves out of the way and make forward motion tough going.

Under the waterline, the stem is pretty sharp. The upper portions of the bows were designed to rise up against the sea and balance a heavily-sparred and extensive forward sail area. This lift would then bring the ‘cutwater’ lower section of the stem into direct contact with the waves, parting the seas to accelerate and maintain speed.

Undergrowth’s effect on boat performance

Leaving aside the menace of shipworm as a specific threat to wooden craft, all vessels are subject to the insidious encroachments of marine life, such as the limpet and the dreaded gooseneck barnacle.

This last was the scourge of Golden Globe Race skipper Tapio Lehtinen, but hull growth, he recognised, is inevitable.

Scrape it off, but keep in mind that it will grow back.

Regular hull cleaning and maintenance will prevent marine life, like barnacles, from taking root, which will slow the boat down. Photo: Christine Favreau / PPL / GGR.

Seaweed and other undesirables impact your boat’s performance to the extent that a yacht which used to corner like a Jaguar at Brands Hatch now handles like a muddy Land Rover in rainy season Uganda.

Hydrodynamically-speaking, your boat’s performance will be improved, and your engine will work most efficiently, when the underside of your craft is at its most slippery.

This applies to the entirety of your vessel’s wetted surface, so the hull below the waterline, as well as the foils (keel and rudder), propeller shaft and prop (or saildrive unit), and not forgetting anodes and even through-hull fittings.

The deleterious effects of marine growth on the hull are manifold: slow speeds, poor manoeuvrability and performance to windward, and burning more diesel when under engine power. Attacking this growth with frequency and energy, using an angled brush, is a good idea.

To try to prevent growth, there are various antifouling methods, like traditional paint and foul-release silicone formulas, biometric coatings, and ultrasound technology (see our article on the latest developments in antifouling).

Blistering

Glass reinforced plastic (GRP), the ‘plastic’ of modern production boats, is not completely water impermeable, as many believe.

It is not like wood, which needs a good soak to assume its shape, ballooning up its strakes to compress the hull frame.

GRP in its wetted state is vulnerable to osmosis.

This is the process whereby water on the outside of the hull is attracted towards the glycol found inside the boat laminate; glycol readily absorbs and retains moisture.

The water is drawn into the glycol, and the two liquids combine to form a new chemical, which can be acidic or alkaline, and smells like vinegar.

Not all blisters mean osmosis, so it is best to get them checked out by a professional. Photo: Will Payne / MBM.

Moisture will continue to be absorbed, and the laminate will break down, and eventually, the moisture won’t be able to escape, causing the blister.

Said blisters damage boat performance in all the ways mentioned above for barnacles and marine life fouling. If there are signs of blistering, make sure you seek the advice of a surveyor.

Not all blisters are osmosis, and often can just be water blisters, which develop between the hull and the coatings, often due to the coatings not being applied properly or the boat being epoxied when the vessel was not dry enough.

Regardless, it is a good idea to get any blisters checked by a professional.

Galvanised into action

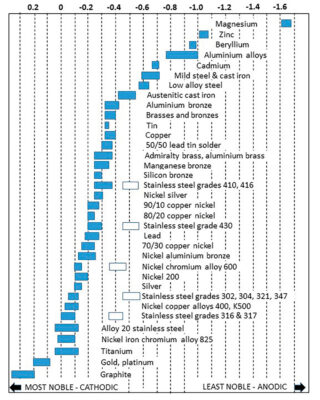

The galvanic series of common metals and alloys. Noble, or cathodic metals to the left, less noble or anodic to the right. Note that metals whose corrosion resistance is derived from a surface film have both passive (surface) and active (substrate) voltages. Photo: Vyv Cox.

More pernicious, probably, than osmosis, is galvanic corrosion.

This is an electrochemical process in which one metal corrodes preferentially when it is in electrical contact with another. Two metals immersed in seawater (an electrolytic solution) form a kind of electrochemical battery through which the current flows, corroding the less ‘noble’ metal (see table right).

Faster corrosion happens when something from a vessel’s electrical circuit leaks some of that current to submerged metal parts. Your prop and shaft are especially vulnerable to this sort of corrosion.

It follows that you need to isolate circuitry and engine accessories from the hull. This can be done with breakers (correctly installed) and switches (themselves isolated).

Underwater corrosivity has the largest impact on boat performance, but corrosion happens everywhere that humidity or moisture can function as an electrolyte.

Pitting on an aluminium spar is one example: corrosion on the exterior could be seen as extremely unlikely to lead to structural weakening or even failure. But a glance inside could tell a different story.

A noble sacrifice

Sacrificial anodes are the answer to galvanic corrosion.

These more-or-less streamlined lumps of metal make their sacrifices by presenting themselves for corrosive attack ahead of the more ‘noble’ metal that they aim to protect.

They’re usually on the prop and the shaft. Those on the prop corrode in place of the prop and are usually on the end of the shaft or on the hub. Anodes also protect the keel, rudder, shaft bracket, and sail-drive.

Sacrificial anodes should be checked regularly to ensure underwater gear, like your propeller, is protected and works at its optimum. Photo: Graham Snook.

If boat performance is to be maintained or improved, vigilance is key: monitor the rate of corrosion on your sacrificial anodes and get them replaced when their effectiveness is waning. This usually takes place during the annual liftout.

Remember that anodes should not be painted, as it interferes with galvanic connectivity. You don’t want a barrier between the anode and the installation that it has been put there to protect.

How screw propellers can help boat performance

Design considerations for an efficient propeller include the shape of the blades, how fat or thin they are, how much they are angled towards the water flow, and in which direction this angle goes.

Propellers are a world of variety, to be selected in accordance with the design properties of a particular vessel.

Folding and feathering props will have corresponding effects on acceleration and deceleration, power transmission, drag and prop walk.

Blades of a feathering prop can be positioned like a flag relative to the flow of water, minimising resistance and reducing drag. Photo: Graham Snook / Future.

A racing yacht will have an entirely different prop for its auxiliary engine than a cruising yacht that might want to move a certain greater tonnage in tight manoeuvres in finger berths.

Twin-bladed props are overtaken by three-bladed ones when it comes to efficiency under engine. But it follows that the greater surface area brings additional drag.

When sailing with the engine stopped and the clutch disengaged, way over the prop will make it rotate.

Usually – and this is not a universal rule – putting the stick into reverse will stop the prop turning. Props turning while under sail make that tell-tale noise, which I call ‘grinding my gears’. To me, it sounds like a jam jar lid slowly being tightened. Hydraulic gearboxes should be stopped in neutral.

If the propeller blades fold inwards when the engine is stopped, that’s great for efficiency.

Generally speaking, a fold is initiated when the engine is in forward and you’re going a maximum of three knots.

But generalisations here don’t really work. Each manufacturer will have their own operating procedures. The alternative to folding is feathering, which is when the blades turn to go completely (or as near as possible) parallel to the flow of water.

Otherwise, if you are sailing along even very gently, you will easily feel the sluggishness introduced by static propeller blades and their traction in the water.

Prop walk

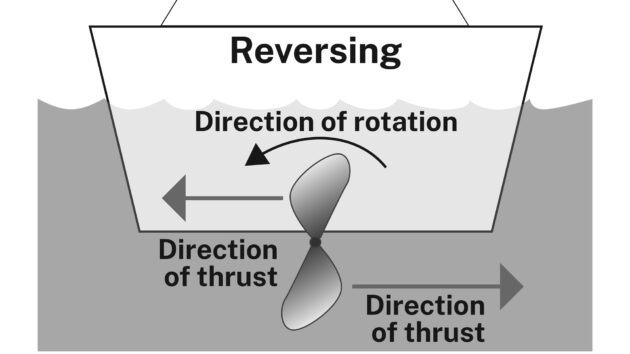

Most yachts’ propellers rotate in a clockwise direction when engaged in forward gear. Prop walk, the ‘paddle-wheel’ tendency of the screw propeller in turning the vessel, can be used to great advantage for efficient manoeuvring.

Prop walk is your friend.

Prop walk is more pronounced when reversing as the rudder is initially less effective, but it also happens when moving forward.

A right-handed prop, generally found in most production yachts of the last half-century, kicks to port in astern (see diagram above). So it can be used to turn in tight.

Reversing into a finger berth at a marina pontoon is easily managed, in most situations, when this prop walk is made use of.

Going astern is a relatively slow movement, and any drifting awry can be swiftly corrected by a burst of forward motion, a powerful and reassuring way to get you out of any trouble or fender-boxing.

A fouled prop can kill your boat’s performance

Keeping the prop clean and free from entanglements or debris will, obviously, always improve your boat’s performance.

You can achieve this as much as possible by always keeping a look out, avoiding areas where lobster pots are laid (if known), paying attention to other boats’ anchor warps and giving fishing trawlers a wide berth.

Keeping a good lookout will help reduce the risk of fishing gear or lobster pot entanglement.

A fin keel or a high-aspect-ratio rudder sticking down into the water like a knife would, on the face of it, be more likely to snag lines or abandoned fishing gear in the water.

It is a smaller piece of equipment, but the fact that it’s rotating and, to a certain extent, drawing up water into its spin, the propeller is much more likely to catch a line than the keel or rudder.

The spinning motion surges the line towards the blades and wraps the prop shaft. The engine labours then stops. The heat generated can melt the line to the shaft.

It is entirely possible, however, that a snatch of material of some sort has interfered with the propeller. It hasn’t been jammed completely, but is most definitely pushing your engine to overheat.

If you suspect you’ve gone over a line in the water, turn off the engine.

An initial response would be to release the clutch, or go into neutral. The snag is instantly less likely to be actively drawn up around the shaft or sail-drive base.

Engaging astern in the hope of ‘unwinding’ the snag is a bad idea. Most probably, a coiled-up line, which may not even have a riding turn, will become a massive, nasty, clumpy knot.

Fitting a rope cutter is prudent, but won’t mean your boat’s propeller will never be fouled.

A detailed examination of the boat, underwater, using a mask and snorkel if possible, is required if safe to do so. If you’ve run over one of your own mooring lines, sheets, or if it’s clearly visible, then a tug against it can often free it from the prop.

Only pull on the rope by hand. You’d be ill-advised to start winching it. If the line cannot be pulled through, then it will have to be physically cut off at the propeller. Diving with a kitchen knife is not recommended if you harbour any doubts about your ability to handle:

1) limited visibility

2) head gashes from hull barnacles or even sharper metal things

3) disorientation.

Submarine heroics aside, should your propeller be freed of entanglement, it may not be the end of your woes. If the engine runs with a newly-noticed shaking on its mounts, then the shaft may be affected, shoved or even bent.

In this case, it is best to make port as soon as possible and perhaps seek a lift-out to see what is going on.

Furthermore, making port under sail power, if at all possible, will preserve the elements of your drive system for inspection and not exacerbate any mechanical issue.

Working back from the prop is best. The stern tube and shaft bracket require close examination, as well as the propeller and its individual blades. For sail-drives, the ring and gears need a good inspection.

An array of rope-cutting devices is available to retrofit or upgrade your boat performance, but they’re not a cast-iron guarantee that your prop will never be fouled.

Ben Lowings has worked for the BBC World Service, has sailed everywhere from the Norwegian Arctic to New Zealand, and skippers commercial yacht deliveries around Britain. He has written three yachting biographies: The Chancellor on George Millar, The Dolphin on Dr David Lewis, and The Sun of May on Vito Dumas.

Want to read more articles on improving boat performance?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter