After draining her charter boat batteries, Ali Wood realises it’s time to get to grips with her marine battery system.

Word to the wise: always keep an eye on your marine battery.

Last summer, I hired a flybridge cruiser on the Canal du Midi. The brief handover focused on how to negotiate locks and the breathtakingly narrow bridges. When I asked about power management, I was advised:

“Plug in to shore power or use the generator if you need it.”

Easy, right?

Having sailed small boats and worked on charter yachts, I figured I was good at managing power. But it seemed I’d bitten off more than I could chew with this 50ft powerboat!

With bow- and stern-thrusters, TV, dishwasher, four showers, a microwave, coffee maker, fridge-freezer and air conditioning, it had more appliances than I did at home… not to mention four adults and three children making full use of them.

Obviously, we drained the batteries the very first night!

A night off-grid in the Canal du Midi requires careful power usage (or the generator). Photo: Ali Wood.

We’d moored alongside the bank where there was no shore power, so we had switched on the generator, which was rather like starting the engine. Boy, was it noisy; would it have been better to run the engine in neutral? I hoped I wasn’t keeping our neighbours awake. I had so many questions:

Was a day’s motoring not sufficient to top up the domestic batteries? Why did some appliances stop working in the middle of the night, such as the fridge, while others, such as the electric toilet pumps, run fine? What was that mysterious intermittent beeping?

With no gauges, other than the battery indicator on the ignition, I became obsessed with starting the engine, and did so several times a night just to check it (which I’m sure didn’t help matters).

Presumably, our starter motor would be OK because it was a different battery (I hoped), but what about the bow thrusters? Anything other than a quick burst tended to trip them, and there was no way I was entering the locks without them!

I fell asleep pondering AC/DC, marine batteries and 12V and 240V systems, and vowed when I returned to the PBO office, I’d give myself a refresher and write this guide…

Smooth running

For a boat’s power system to work smoothly, you want it to:

1) supply and store battery power when mains electricity is unavailable

2) charge the battery and convert it to the correct type of power for the appliance

3) control and monitor your power usage

There are several ways to get power to your boat: through its batteries, shore power, a portable marine battery charger, a generator and renewable energy sources such as solar panels or hydro power.

The power that reaches your instrument or appliance will either be delivered as 12V or 24V direct current (DC) via the boat’s batteries or as an alternating current (AC), which is what you get at home on the global electricity grid, commonly at 50Hz or 60Hz frequency and 220-240V.

Marine batteries deliver DC, so to use appliances that run on AC power, you’ll either need an inverter, which converts AC to DC, or plug in to 240V shore power with a cable.

Most boat systems run on 12V to power electronics such as chart-plotters and radios, as well as appliances. On larger leisure boats, however, you’ll often find 12V and 24V systems, as well as a 240V shore power system.

Marine batteries

The engine charges your marine battery via the alternator, which generates AC power (hence the term ‘alternator’) and converts it to DC. When charging, the battery output tends to be around 14V, and when resting, around 12.5V. Note, though, that the alternator is primarily designed to charge the starting battery, particularly with outboard engines, so it may not provide a complete deep cycle battery recharge.

Both petrol outboards and diesel inboards use alternators to charge batteries, though outboards have a small alternator with a much lower output, typically around 2-3A.

While motoring once on an eight-hour passage to Poole, I noticed the rev counter on our Maxi 84 drop mysteriously to zero. However, the Volvo diesel engine kept running, and there was no drop in speed.

It turned out our alternator had failed, so the rev counter was no longer getting a feed. Without the alternator, the charge soon dropped from 13.4V to 12.7V. A low state of charge in lead-acid batteries is bad news – if they fall below 11.4V, they’re unlikely to be revived. We immediately switched off our autopilot and instruments, to prevent further loss, and later had the alternator refurbished.

The alternator on Maximus failed, meaning no charge was going to the batteries. Photo: Ali Wood.

Which type of marine battery?

Boats typically have two kinds of batteries: starter (or crank) batteries for starting the engine, and house (or domestic) batteries for powering everything else. This way, you should always be able to start your engine, even if your house batteries have run down.

“Making a lead-acid battery is like making a cake,” says Stuart James of Predator Batteries. “It’s all to do with the ingredients and the quality of those ingredients. It’s actually quite an art, and you can make it dead cheap and a load of rubbish or with varying grades of quality.”

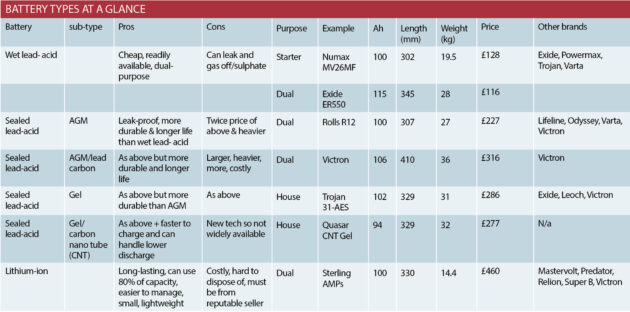

Stuart explains that there are essentially two types of marine battery: lead-acid and lithium-ion.

Commonly used to start the engine, a traditional ‘wet’ or ‘flooded’ lead-acid battery is the cheap and cheerful type you buy from automotive stores, and has liquid electrolyte sloshing around in it.

Next, you have sealed lead-acid, which comes in two forms – absorbed glass mat (AGM), where the battery plates are protected by fine-stranded glass mats – and gel, where the liquid electrolyte has been converted into a gel. While AGM batteries can be used for the engine and house applications, gel batteries are better suited to house applications.

Lead carbon batteries, though not widely sold, are AGM batteries with a little more carbon. Though more expensive, the carbon protects them from degradation caused by PSOC (partial state of charge).

The newest addition to the marine battery market is the carbon nano tube (CNT), an improved gel battery, which is more durable and can withstand lower discharges.

“If you have a 100Ah lead-acid AGM you shouldn’t take it below 60% depth of discharge,” says Stuart, “but with a gel battery, you can take out more Ah without damaging it, so can start with a lower capacity battery. A gel battery is far better over its lifespan than an AGM.”

Starter batteries are designed to handle a high current output for short periods, while house batteries are ‘deep-cycle’, meaning they can handle lower outputs for an extended period in order to power appliances and systems.

Exide 115Ah dual-type batteries are capable of cranking or leisure. Photo: Ali Wood.

Dual-purpose or hybrid batteries are designed to balance both these needs, meaning you can have two or more of the same type of battery in a ‘bank’, each doing different jobs, and either could be used for starting the engine.

Even if the batteries are the same type, it’s good practice to have two battery banks, so that one can be reserved solely for engine starting, while the other is used for domestic loads. Some vessels may have a third bank for a windlass, bow-thruster or other high-power devices.

Each bank may comprise just a single battery, or several batteries connected in parallel. In larger yachts with 24V electrics, batteries are connected in series to double the system’s voltage.

Split charge diodes allow more than one battery bank to be charged without the need for any manual switching.

However, as PBO’s Rupert Holmes points out, there’s a voltage drop of around 0.7V across the diode, which saps a significant amount of power before it ever reaches the batteries.

Potential solutions to this problem include adjusting the alternator output, adding a rotary battery switch, or using voltage- sensitive relays (VSRs).

A VSR automatically connects and disconnects two batteries based on the voltage level of the charging system.

There have been huge advances in marine batteries in the last decade, with more and more boat owners switching from lead-acid to lithium. Unlike lead-acid batteries, which can suffer from over- or under-charging, lithium batteries can handle higher charge and discharge rates and offer faster charging times compared to traditional deep-cycle batteries.

However, there are drawbacks too, when it comes to disposal and reputable sellers, as Stuart James points out in his industry insight into lithium marine batteries.

Stages of charging

Sometimes it’s difficult to know if a battery is charged because the voltage shoots right up as soon as you start the process, but when you disconnect the shore power or stop the engine, it drops again. It’s therefore handy to know the three stages of charging a lead-acid marine battery.

These are bulk (where the battery charges at a constant rate to about 70%, taking around 5-8 hours), exhaustion (the remaining 30% takes 7-10 hours) and float (the final stage, where batteries are maintained at a set lower level to compensate for self-discharge).

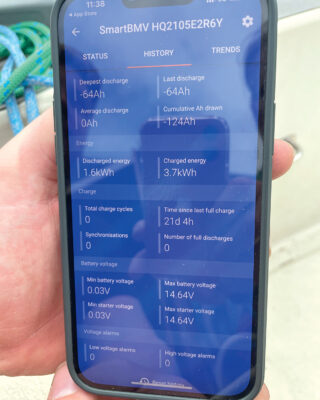

The Victron app will provide you with the power draw for each item on board. Photo: Ali Wood.

On PBO Project Boat Maximus, I’d seen the batteries climb up to 14.5V during (both from shore power and from the alternator) and later drop to float around 13.4V. With a smart monitor, you can see this information displayed on the boat and also on your phone, so it’s easy to spot if there’s a battery charging issue.

Marine battery cycle life

Batteries don’t last forever. There’s an important distinction between shelf life – how long an inactive marine battery can be stored before it becomes unusable (ie having only 80% of its initial capacity) and cycle life – the number of times the battery can completely charge and discharge (one cycle) before it becomes unusable.

For a lead-acid battery, lifetimes of 500 to 1,200 cycles are typical (double for lithium-ion batteries), but the ageing process results in a gradual reduction in capacity over time.

There are other factors affecting cycle life, such as temperature (the ideal temperature is 10°C or less, which isn’t easy to achieve on boats, especially if the battery is in an engine room), capacity, and age. All sealed lead-acid batteries will eventually exceed their life expectancy.

The number of useful cycles any battery will give you over its lifespan is also governed by how low you take its charge each time, and how quickly you take the power out. This is known as Depth of Discharge (DoD).

Cold cranking amps (CCA) is the number of amps a battery can support for 30 seconds at a temperature of 0°C before the battery voltage drops to unusable levels.

When comparing starter batteries, this can be a useful consideration, especially in colder climates. Replacement batteries should equal or exceed the original battery’s CCA.

A smart marine battery monitoring system helps you keep tabs on your power. Photo: Ali Wood.

Doing the sums

Before upgrading batteries, it’s worth looking in detail at your power needs.

A more powerful appliance uses more amps (the flow of electrons through a circuit) and has a higher wattage (the rate that energy is consumed). So, for example, a 2,500W electric windlass (200A) might consume electricity at a rate 100 times higher than a 25W light bulb (2A).

Every piece of electrical equipment on a boat should have a label or manual that explains either its demand for amps, its output in watts or both. Knowing this can help you make decisions about marine battery capacity. It helps to know the following equations:

Volts x Amps = Watts

(example: 12V x 6A = 72W)

Watts ÷ Volts = Amps

(example: 300W ÷ 12V = 25A)

Amps x Time = Ah

(example: 2.5A x 5h = 12.5Ah)

Think about your daily routine. Do you turn your fridge on as soon as you step aboard, or instruments when you leave the dock? What time will the lights come on and off? Next, consider passage making. You may need to account for having the VHF on standby, MFD for chartplotting, plus other instruments, autopilot and nav lights for a night passage.

You can work out your boat’s power draw with a multimeter or, if you have a battery monitor, turn on the items one at a time and read the current draw. If you’re starting from scratch, then you can source the power rating (in watts) or current draw (in amps) from each item, as I did for Maximus (see PBO March 2022).

Marine battery charge and capacity

Ali’s charter boat moored up on the Canal du Midi. Photo: Ali Wood.

The more things you need to power up, the larger capacity batteries you’ll need, but there’s still a balancing act to be done. Too little capacity means you’ll be constantly recharging, but if your batteries are too powerful, you may never be able to fully charge them, which will shorten their life.

Neither can you leave batteries uncharged for too long. A lead-acid battery discharges and can become sulphated, and while most will charge within five or six hours, the last 10% can take another eight to 12 hours, and over time this becomes progressively harder.

For most sailors, this is impractical, but with lithium batteries or a high-quality sealed lead-acid, solar power will take care of the last bit of charging as long as you have the right regulator.

It’s important to charge the batteries at least once a month, but note, the very act of starting the engine will draw a considerable amount, so a shore power charge is better.

Powerboat setup

Returning to the French charter boat with its numerous appliances, could it be that different items ran off different systems?

I suspected that the thrusters, engine and generator would have different batteries from the house appliances, and that these too might work from different batteries, depending on their consumption. When I dug deeper and found the boat’s specification (see panel, below), I finally understood this was the case.

Having mod cons means planning power consumption carefully. Photo: Ali Wood.

The fridge had a separate battery from the other services (and typically stopped working first), and the dishwasher was powered by the generator, which we only used once. No wonder we had to unstack it and wash the dishes by hand… first world problems, I know (who really needs a dishwasher on a boat!) but it was another thing to think about on a relaxing holiday.

Fortunately, spring in the Med provided the perfect climate, requiring neither air conditioning or heating, but had we chosen to use those, we’d have needed the generator or shore power.

It seems obvious now that I’ve done my research, but as I was more accustomed to small boats with cold water, a single-burner hob and bags of supermarket ice to keep provisions cool, this was all new for me. It certainly would have given me peace of mind to know that running the fridge flat wouldn’t impact any other systems.

Shore power

Shore power is your yacht’s second electrical system, allowing you to bring AC electricity on board using a cable, with the male connector plugging into the power outlet on the pontoon and the female connector plugging into the vessel. This is converted to DC to charge the batteries, or can be delivered directly as AC to low-wattage appliances (ideally no more than 2kW) with standard three-pin plugs like you get at home.

On Maximus, we connected the shore power to our Victron Phoenix IP43 battery power, which converted the mains AC input to DC. We then used a battery monitor to measure parameters such as voltage, current, state of charge, amp hours and the time to charge or discharge.

I could check this on the Victron app on my smartphone, and was able to identify any marine battery charging issues. For shore power to be sufficiently charging, you’d expect to see between 13.6V to 14V.

A shore power lead allows you to use AC appliances. Photo: Ali Wood.

However, I once returned to Maximus to find the batteries at 12.4V, and when I checked my app, I saw that the shore power had not worked for 21 days! I checked the cable connection and realised it was my error – I hadn’t screwed it in tightly enough. Another week or so and I’d have run it down.

Using an inverter for marine battery charging

Inverters allow for steady mains power from a suitable bank of batteries, even on the smallest boats. These transformers ramp up the power from 12V or 24V DC to 230V/50Hz, necessary for running mainstream appliances such as televisions, power tools and computers.

In fact, you can make use of any domestic appliance you can ashore, from microwaves to hairdryers.

Many inverters also recharge the batteries when the boat is on shore power.

A good starting point is to decide how many mains appliances you want to run, and see if any can use a direct DC supply instead (such as a phone charger) and then select a unit that will supply the peak power you need with the batteries available. Inverters are quite punishing on batteries, so if you’re thinking of upgrading the battery bank, do this at the same time.

An inverter allows the use of AC appliances like this microwave on a transatlantic catamaran. Photo: Ali Wood.

You can choose high-quality fixed inverters that have built-in battery management facilities or smaller, portable units for dedicated items such as laptops.

There are two main types of inverter: modified sine wave, which is cheaper and less powerful, and pure sine wave.

The latter will power just about any AC appliance and is particularly useful for devices that can suffer from interference, such as radios. While grid power can fluctuate, or even drop below 180V, a pure sine wave inverter protects your equipment against failure.

Portable solutions for marine battery charging

If you’re frequently away from shore power and don’t have an onboard charging system, you’ll need to use a portable marine battery charger. Modern onboard chargers support lead-acid, AGM and lithium-ion batteries.

Features to consider include whether it’s waterproof, has automatic battery detection (minimising the risk of user error) and temperature compensation (adjustable performance based on ambient temperature to prevent overheating).

Ali hadn’t understood how long the Nanni diesel generator needed to run

to recharge the batteries. Photo: Ali Wood.

Portable chargers work both on and off the boat. Simply connect the charger’s clips to the battery terminals (positive to positive, negative to negative) and plug the charger into an AC power source, whether that’s at home or the marina shore power. The charger will automatically adjust the charging process based on the battery’s needs, shutting off when done.

Note, the charger must have the same voltage as the battery bank, and the different types of batteries are charged at different rates. You press a button to set the charger to the right one.

A rule of thumb, according to Mastervolt, which produces the EasyCharge Portable, is that 25% of the battery capacity is sufficient to safely and quickly charge batteries while still supplying power for consumption. For example, a 50A battery charger is sufficient for a 200Ah battery. For faster charging with gel batteries, increase this to 50%, and for lithium-ion, 100%.

Generator

If you need more mains power than an inverter can provide by itself, a diesel generator will be a huge help. A generator turns mechanical energy into electrical energy, providing electricity to appliances when you’re off-grid and allowing you to charge batteries.

There are two basic types – those that provide 240V AC, and smaller, lighter DC units that are simply battery chargers.

PBO’s motorboat expert, Jake Kavanagh points out that a competent DIY enthusiast can retrofit a generator, and some companies, such as Fischer Panda, will allow this without invalidating the warranty so long as it can inspect the finished job.

“The key to success is having an enclosure in the boat with a stable floor, to allow the genset’s anti-vibration feet to work properly. You’ll also need a supply of clean diesel, good ventilation, a water intake and an exhaust pathway,” says Jake. “You are essentially fitting another diesel engine into your boat, so you also need to consider trim.”

Ali was grateful for the thrusters in the tight locks of the Canal du Mid. Photo: Ali Wood.

A common mistake, according to Stuart James of Predator, is not running the generator for long enough. For example, with an engine, it might take five hours or more to keep appliances charged. “Nowadays, a lot of people have inverters; they want to boil a kettle using electricity rather than gas, but the electricity comes from the battery through an inverter, and that takes a lot of power, meaning you have to charge it more,” he adds.

Many cruising boats carry a small portable generator these days, especially those doing long passages such as the Atlantic Rally for Cruisers (ARC).

Models vary in power output and noise, with newer, more expensive brands tending to be noticeably quieter.

Carolyn Shearlock, liveaboard author of boatgalley.com, says the Honda 2200 is one of the more common brands, and though there are ones that offer more power for less money, the big differences are noise level and size.

“You do not want what’s called a construction generator – the noise is just obnoxious,” she says, adding that generators weigh about 18kg and can be used to charge batteries, run a watermaker or power tools.

Renewables

With a free (if not always consistent) supply of wind, sunshine and water to provide power, the only challenge in fitting renewables is cost and space, but once you’ve installed them, they’ll keep your marine battery set-up topped-up, and in some instances (particularly with solar), can be enough to power the whole boat.

Hydrogenerators contain an impeller (reverse prop) that rotates when dragged through the water, providing consistent performance as long as you’re moving. Wind chargers provide excellent performance even at low wind speeds. Some forms of windvane self-steering, such as

Hydrovane, have a mounting bracket for a hydrogenerator so it can be used to recharge the boat’s batteries while steering the boat.

The Hydrovane self-steering system can also work with a hydrogenerator. Photo: Sharone Ee.

Solar technology has improved greatly in recent years, with the introduction of flexible solar panels, which you can walk on, and cleverly designed frameworks that allow you to move them with the sun’s arc. Even over the winter, a solar panel left on a boat in the yard can be sufficient to stop the batteries from discharging, which we found was the case with Maximus.

The more you can top-up with renewable energy, the less money you spend in the long-run on fuel or shore power connections. It’s far less hassle to let nature do what it does best, and means you can be self-sufficient at anchor, no longer relying on marinas.

Lithium iron phosphate batteries: myths BUSTED!

Duncan Kent looks into the latest developments, regulations and myths that have arisen since lithium-ion batteries were introduced

Why is my boat battery not holding a charge?

Chris Mardon is struggling to understand why his boat battery is not holding a charge. Duncan Kent has some suggestions

What battery capacity? Working out your boat’s power requirements

In order to work out your boat’s battery capacity you need to know how much power you’re going to draw,…

Adding a second battery to a boat

When I bought her new, my boat had just a single 75Ah domestic battery, best described as adequate if you…

Want to read more practical articles like this?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter