Charles Beddingfield's classic yacht's old BMC 1.8 diesel engine was smoking badly. Rather than shell out for a new engine, he stripped and rebuilt the old one for a fraction of the cost of a replacement.

When I started Tudor Rose’s old BMC (British Motor Corporation) 1.8 diesel engine one windless summer morning, a dense pall of grey smoke lingered incriminatingly over the anchorage. I slunk away to sea hoping no-one would notice.

The overhauled engine was tested at home (a temporary fuel supply and exhaust pipe have been rigged and a hose is supplying cooling water) before it was installed back in Tudor Rose. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

The problem had crept up gradually over a few years until now there was still some smoke even when the engine was hot. It could no longer be ignored.

There could be several causes, but at season’s end when Tudor Rose was laid up for winter, compression tests confirmed that it was, in any case, time to hoik the engine out and give it a decent overhaul.

The easy solution would have been to discard the old lump and pay for a nice, shiny new one, but not everybody’s budget runs to such extravagance.

Besides, no matter how wealthy you may be, simply buying new might be questionable when you consider the environmental cost inherent in a new engine’s manufacture.

The engine was initially lifted a few inches off its mount using a lever hoist for good control, to check the sling before being lifted out. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

So I prepared the ground by disconnecting electrics, fuel pipes, control cables, propeller shaft and the like.

Then along came Steve, the trusty yardman at ABC Powermarine in Beaumaris, Anglesey, with his JCB telehandler to demonstrate expertly that there is nothing half so much worth having as the right tool for the job.

After helping me lower Tudor Rose’s Broads-style collapsible cockpit canopy, Steve lifted the engine with infinite care off its beds, out of the boat and into my little red trailer to be towed home for preparation.

Time to dress down my diesel engine

Engineering work would be cheaper if Charles Beddingfield first stripped down the motor. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

Suspicious of engine reconditioners found online who gave no physical address, I found a local company to do the work.

They told me that the more I stripped down myself, the less I’d be charged for dismantling, so I undressed the engine of all external paraphernalia such as starter motor, alternators, manifolds and gearbox.

I highlighted the timing marks on the flywheel, injector pump and valve timing sprockets with bright paint for easy realignment later, and made a flywheel immobilising tool to help with undoing the flywheel bolts and front pulley nut, which are very tight.

I also removed the cylinder head so that I could examine the bores to form an idea of what I should expect the machine shop to do.

Timing marks were highlighted on the timing chain sprockets for easy realignment. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

The only problem when stripping down was a seized bolt in the timing chain cover, which snapped off. The stump eventually yielded to repeated bouts of heat from a blow lamp and wrangling with Mole grips, saving the thread in the engine front plate, which would likely have been destroyed if I’d had to drill the stump out.

Assessing the effect of time on my diesel engine

Charles fashioned a simple flywheel locking tool to undo the very tight flywheel bolts and front pulley nut. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

The diesel engine is more than 50 years old, so I expected to see signs of wear.

The compression tests, with a hot engine, showed all cylinders remarkably similar (which is good), but all on the low side at about 280psi (not so good).

After dosing each cylinder with a teaspoonful of oil down the injector hole, the compressions all improved to about 315psi, a 35psi improvement.

These signs point to excessive blow-by of the pistons rather than valve or gasket trouble. Even so, the engine was not burning excessive oil.

With the head off, the bores, visually, still showed faint signs of the original cross-hatched honing marks, together with a faint yellowish discolouration.

I read these signs to mean that the bores were not in fact very worn, but they were showing signs of the dreaded bore glazing phenomenon, that faint yellowish discolouration, which, together with low compressions pointing to worn piston rings, was probably a contributing factor to the engine’s embarrassing smoke, harder starting and somewhat ragged running on cold startup.

These cross-hatch honing marks normally help hold oil to lubricate pistons and rings, and when they get worn away or filled smooth by hard glaze, the engine loses compression.

The engine was compression tested, which showed a drop in psi, explaining part of the poor performance. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

My diesel engine normally operates at no more than half throttle and has been run for the last 500 hours using cheap semi-synthetic lubricating oil, which may well have contributed to these effects.

PBO expert Vyv Cox (coxeng.co.uk) has instructive things to say about this, and in future, I’ll take more trouble to find oil of the correct API specification for this older, lightly loaded diesel engine, despite the higher cost of that oil.

The main event

Having undressed the diesel engine, I handed over the block to the machine shop with instructions that it did not need to be fully reconditioned to as-new factory spec, which might easily have cost twice the eventual bill.

Some of the original honing marks were still visible in the bores. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

Instead, I asked them to do only enough work to keep the engine running satisfactorily for another five to 10 years (500 to 1,000 hours) at a more economical cost. I wanted to restore the lost compression, fix oil drips, renew the timing chain and have the valve guides and crank assessed for wear.

I half expected a great sucking of teeth and much shaking of heads, but in fact they seemed quite enthusiastic about the project. However, I made a rookie error in remarking casually that there was no great rush as we had all winter to do the job.

Of course, they took me at my word, and I did not get the engine back until very late the following spring after nagging them for completion.

After examination, the engine shop recommended re-honing, new piston rings, sleeving the rear oil seal journal, crankshaft polish and new main bearing and big end shells to restore critical tolerances. All that was expected, but they also pointed to a slightly worn camshaft lobe.

The re-honed cylinder bore. The cross-hatch marks are clearly visible. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

I contacted Calcutt Boats, which stocks a good range of BMC spares. One of their representatives told me it is common to find one or two cam lobes worn, apparently at random, in these engines.

It could supply a new camshaft for the later version, but not mine, being the earlier and now rarer type with different journal sizes.

The wear was so slight that I might have ignored it, but after some humming and hawing, I found a ‘new old stock’ replacement camshaft from Vintage & Classic Car Spares (vintageandclassicspares.co.uk) for £150 plus VAT – an absolute bargain.

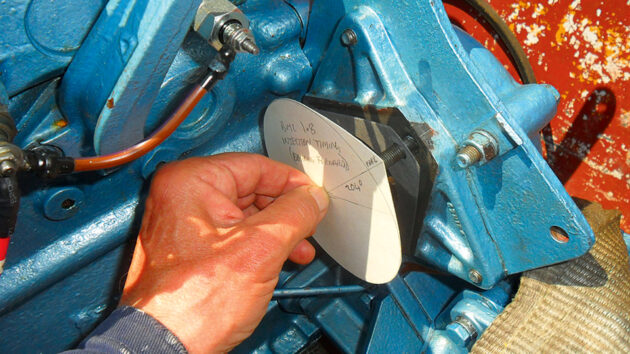

A timing tool for the BMC 1.8 engine was not available, so Charles made a cardboard timing disc to check timing marks. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

While the engine was away at the machine shop, I cleaned and repainted all the ancillaries, ordered additional parts such as a timing chain, water pump and hoses, and when the engine came back I refitted everything before trailering the refurbished engine, resplendent in new paint, back to the boatyard where Steve craned it back aboard for me.

Injector puzzle

As well as the general refurbishment outlined above, I suspected a failing injector and bought a new one from Calcutt Boats, which diagnosed that the existing injectors were the wrong type altogether, so I ended up buying a completely new set.

How this came about is a mystery, but I had sent the old CAV injectors to another firm a few years ago, and assumed that my own injectors had been sent back, duly refurbished. Perhaps it sent back a different set in error. They all looked identical externally, but Calcutt told me there is a difference in the calibration of nozzles for different diesel engine models.

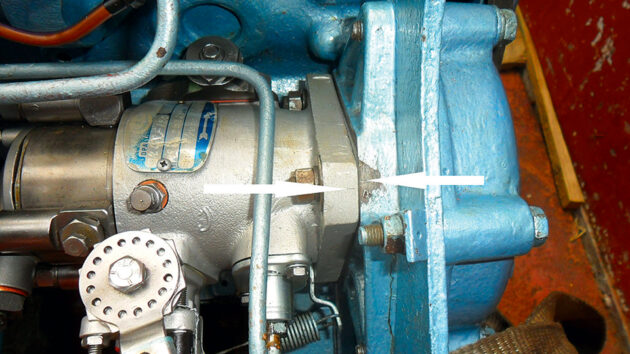

Displacement of the scribed marks shows the advance needed to correct the injection timing for internal wear in the pump. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

Hey ho! Having renewed the injectors, I went the whole hog and replaced the injection pump too. The old one was working okay, but these things do deteriorate with age, and heaven knows when it was last serviced.

In the course of all this, we found that it was necessary to advance the injection timing by about 2° because, I suspect, internal wear slightly retards the pump’s timing. It would be good to have an expert’s view on this, but incorrect or delayed injection timing is one cause of white smoke and rough idling from a diesel engine.

The valves only need lapping in. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

The upshot

Once we understood the correction to static timing, the engine ran smoothly and cleanly.

Repeating the compression tests after a full season’s operation showed a significant improvement to around 380psi, and the Tudor Rose can now start up on the stillest of mornings and proceed proudly to sea with her stemhead held high and not even a whiff of that embarrassing cloud of smoke. Hurrah!

A newly honed cylinder bore needs running-in just like a brand-new diesel engine. Opinions differ as to the best regime. I put the engine under load as soon as possible after a cold start to get it up to proper temperature, and ran it a little harder than I normally would – about three-quarters throttle – for the first 20 hours, then at 50 hours changed the oil to flush away the resulting metallic contaminants, refilling with the recommended API SE/CC grade oil for this older engine.

The yellow sector marks the correct static injection timing. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

This is harder to find and costs two or three times more than the cheap oil you can buy at the supermarket that claims to be suitable for all diesel engines.

However, it is of a brand intended specifically for marine diesel engines, with pictures of narrowboats on the label to inspire confidence, rather than go-faster stripes or flashy logos.

There are engine shops all over the country that are equipped (or have the contacts) to tackle diesel engines of almost any type or make, from simple deglazing to a full reconditioning at very reasonable cost.

Deglazing, for example, is only about £10 per bore, plus any parts and time for dismantling and reassembling if you cannot do this yourself.

Or you could buy the honing tool from Machine Mart for about £25 and do the whole job yourself. In hindsight, I might have done that – it would have been quicker and less bother than finding a company to do it.

Following the work, Tudor Rose’s engine now starts easily and has a clean exhaust. Photo: Charles Beddingfield.

Before condemning a diesel engine to the scrap heap, it is worth considering if you can overhaul it yourself. It makes use of winter downtime, and it is very satisfying to fire up a reliable, smooth-running and efficient diesel engine, made so by your own efforts and gumption, while resisting the creation of unnecessary manufacturing pollution for the grandchildren.

I mean, where’s the achievement, or the virtue, in just ordering a new one?

Total costs including labour, vat, and delivery

- De-glaze/re-hone bores, new piston rings, polish crankshaft and replace bearing shells, refurbish oil seal journal, top and bottom gasket sets £1,221

- Timing chain, water pump, hoses and oddments £145

- Cranage £66

Total £1,432

To that, I also added as luxury extras, not strictly essential:

- New camshaft £190

- Injectors £200

- Injection pump £300

- Additional total £690

So the whole project cost £2,122 – painful, but still half the price of a reconditioning job, and one-third of the price of a new diesel engine which would likely also need some alterations to engine mounts, fuel and water pipes, electric wiring, shaft coupling etc.

Diesel engine parts sources

BMC engine parts from Calcutt Boats, calcuttboats.com. Special thanks to Douglas and Kate for their patience, help and speedy service.

Camshaft from Vintage & Classic Car Spares, vintageandclassicspares.co.uk. Thanks to Warren Grove.

Oil to CC grade from Midland Chandlers (www.midlandchandlers.co.uk) at Preston Brook. I often find the inland waterways chandleries a good source of useful things, from special oils to non-slip table mats. Halfords (www.halfords.com) also does a CC grade oil.

Engine paint was ordered on Amazon as local suppliers didn’t stock my colours.

Haul out, crane and yard facilities by ABC Powermarine (www.abcpm.co.uk), Beaumaris. A big shout out to Steve and Mitchell, whose care and expertise in handling boats about the yard are always meticulous.

Charles Beddingfield learned to sail as a boy and has built, refitted or just owned a variety of boats, learning something new from each. The Tudor Rose was built by his father in the 1970s and subsequently refitted by Charles. Now retired, and having enjoyed enough nights at sea shivering in the open cockpit of a Folkboat, Charles has sworn never again to put to sea in anything that lacks a decent wheelhouse. He and the Tudor Rose currently moor at Beaumaris and enjoy gentle pottering about the Menai Strait and Anglesey.

Replacing your boat’s engine mounts

Marine engine mounts are designed to isolate engine vibration noise from the boat’s structure. They’re susceptible to diesel and water…

How I found the right electric engine for my boat after spending £25k

Felix Marks explains how he turned around the disastrous electric engine installation on his Tofinou day-sailer

Want to read more articles about diesel engines?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price.

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals.

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

-

-

-

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial, in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

-

-

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and Twitter